Delia (Emily Louisa) Page-Turner, 1892-1976, later Mrs John McClintock Clive

Delia Emily Louisa Blaydes (Page-Turner) was

born 6th August 1892 and baptized St Pauls Bedford in the same year.

Died in 1976, she was the 12th child and 8th daughter of Frederick Augustus Blaydes Page-Turner 1845–1931 and Alice Caroline Dyer 1850–1925

Attended Miss

Susan Cunnington’s Wiston’s School at 10 Montpelier Crescent Brighton. Miss

Cunnington the head and founder was a lesser-known suffragette.

A suffragette was a member of an activist

women's organisation in the early 20th century who, under the banner

"Votes for Women", fought for the right to vote in

public elections in

the United Kingdom. The term refers in particular to

members of the British Women's

Social and Political Union (WSPU), a women-only movement founded in 1903 by Emmeline Pankhurst, which engaged in direct action and civil disobedience.

It is possible

that much of Delia’s strong-willed individuality was shaped by her encounter

with Susan Cunnington whilst at Wiston’s school. Delia developed a love of art

and design & Drama & was an accomplished artist working in oils and

watercolours. She was a horsewoman.

Little is known

about Delia's secondary education but the next big change in her life was her

involvement in World War I as a Nurse. In Delia's personal photography album

and scrapbook, there are many references to her participation as a Nuse both in

the UK and France.

In the 20th

century, Waverley Abbey was owned by the Anderson family. Rupert Darnley Anderson, son of Thomas Darnley Anderson of Liverpool, inherited it from his

brother Charles Rupert Anderson in 1894. His father had purchased it around

1869. During the First World War the house was the first

country house to be converted into a military hospital. It treated over 5,000

soldiers. The Commandant, Mrs Rupert Anderson (the owner’s wife), was awarded

an OBE.

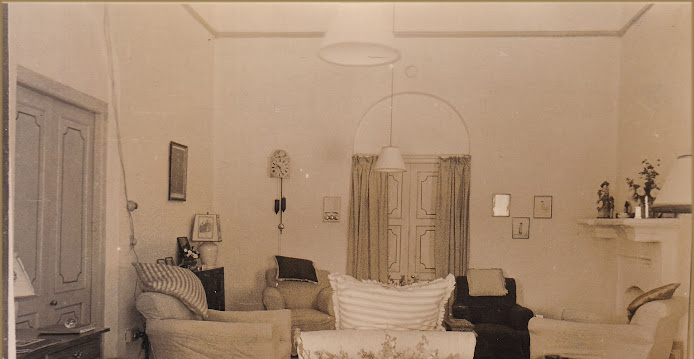

The spacious drawing

room and all the other rooms on the first floor will be occupied by the

patients, and the staff will include a matron and six trained nurses and

members of the Farnham detachment of the Red Cross Society, of which Mrs.

Anderson is commandant, and others.

Following the

First World War outbreak, the British Red Cross formed the Joint War Committee

with the Order of St John. They organised nursing staff in the UK and abroad to

support the naval and military forces. Delia Page-Turner was 1 of many young

women who volunteered to help with the wounded soldiers from the front in England, France and Belgium.

Voluntary

nurses – better known as Voluntary Aid Detachments (VADs) – were people who

willingly gave their time to care for wounded patients. VAD members were not

entrusted with trained nurses’ work except in an emergency when there was no

other option. At the start of the war, VADs were known to have ‘fluttered the

dovecotes of professional nursing’ due to their enthusiastic desire to nurse

wounded soldiers.

The

Base Hospital was part of the casualty evacuation chain, further back from the

front line than the Casualty Clearing Stations. They were manned by troops of

the Royal Army Medical Corps, with attached Royal Engineers and men of the Army

Service Corps. In the theatre of war in France and Flanders, the British

hospitals were generally located near the coast. They needed to be close to a

railway line, in order for casualties to arrive (although some also came by

canal barge); they also needed to be near a port where men could be evacuated

for long-term treatment in Britain.

There were two types of Base Hospital, known as Stationary and

General Hospitals. They were large facilities, often centered on some pre-war

buildings such as seaside hotels. The hospitals grew enormously in number and

scale throughout the war. Most of the hospitals moved very rarely until the

larger movements of the armies in 1918. Some hospitals moved into the Rhine

bridgehead in Germany and many were operating in France well into 1919. Most

hospitals were assisted by voluntary organizations, most notably the British

Red Cross.

Constance Duchess of Westminster British peeress and

socialite Constance Edwina Lewis (1875-1970) sponsored a military hospital in

northern France, which was housed in a local casino in, Le

Touquet.

The hospital was opened by

Constance, the Duchess of Westminster at a former casino with her own money and

donated funds. Le Touquet was a fashionable seaside town, and with surrounding

woods and golf courses, it had been a popular holiday destination before the

war. The No. 1 British Red Cross Hospital was a Base Hospital and took

casualties from the front lines Casualty Clearing Stations. Le Touquet was very

close to Etaples, which was a massive British base with over twenty hospitals.

The No. 1 British Red Cross

Hospital was quite a small hospital, with only four wards and 150 beds. Wards A

and B were spacious and bright, clean and tidy. The chandeliers were wrapped up

in protective cloths with screens on frames around each bed. Although set up

initially for all ranks, the hospital soon took in mainly officers, who

received a greater degree of privacy.

The mix of nurses and VADs

(identifiable through their Red Cross) is required on the wards.

As well as four wards the

hospital had a laboratory and an X-ray department. Captain Stone was the

radiographer. Nine medical officers of the medical staff, including Colonel

Watson, the Commanding Officer.

Constance, the Duchess of

Westminster, the patron of the hospital, also took an active role as a nurse.

In a newspaper, she was described as ‘an excellent masseuse’ along with two

nurses, Miss Richmond and Miss Molesworth.

Entertainment

The hospital seems to have

placed a high emphasis on lifting the spirits of the men they cared for, as

well as for the staff themselves. This may be seen in the number of diversions

they held. These diversions included sports and Amateur dramatics, Inter-troop

wrestling, and Equestrian activities.

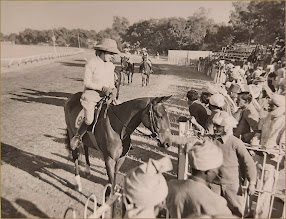

In May 1916 the army put on a

Programme of Sports which involved some of the cavalry. This included a;

jumping competition, inter-troop wrestling (on horseback) and a tug of war

(dismounted). Another concert, held on 13 June 1916, featured the Convalescent

Camp Band. The finale was a rendition of a patriotic song – 'Our Flag'.

Their initial purpose was to

support military and naval medical services during wartime. However, it was

soon realised that detachments could play an important role in caring for the

large number of wounded soldiers during the First World War. When the Joint War

Committee took control of the VADs and trained nurses, these two departments

were placed under the direction of Dame Sarah Swift, who had been matron of St

Guy’s Hospital.

From the outset

of the war until November 1918, trained nurses were sent abroad at short notice

under the banner of the Red Cross. Over 2,000 women offered their services in

1914, many declining a salary, and from this list, individuals were despatched

to areas of hostility including France, Belgium, Serbia and Gallipoli. From

1915 onwards they were joined by partially trained women from the VADs who were

posted to undertake less technical duties.

Membership of

the detachments grew still further on the outbreak of the First World War when

the Joint War Committee was formed. VADs had to be between 23 and 38 years old.

Women under 23 were rarely registered as nurses with the Red Cross, but the

rule was not enforced for women over 38 who had no diminished capacity. From

the beginning of the war until the armistice, trained nurses were always

available to be sent out by the Red Cross. Partially trained VADs, working

under the Joint Committee, carried out duties that were less technical, but no

less important, than trained nurses. They organised and managed local auxiliary

hospitals throughout Britain, caring for the large number of sick and wounded

soldiers arriving from abroad.

Training was at

the heart of the VAD. During peacetime, the volunteers practised their skills

by helping in hospitals and dispensaries and running first aid posts at public

events. When war broke out, they were ready to use these skills. A few VADs had

already gained experience in nursing during the Balkan wars. The number of

volunteers increased dramatically in the early years of the First World War and

by 1918 there were over 90,000 British Red Cross VADs. Number of detachments on Foreign and Home

Service in 1915: Number of detachments on Foreign and Home Service in 1915: 7th

January 1915: 217 Detachments on Foreign Service, 118 Detachments on Home

Service 30th June 1915: 371 Detachments on Foreign Service, 915 Detachments on

Home Service.

Delia Page-Turner with VAD colleagues

During the war a new system of ‘Special

Service’ supplied Red Cross nursing members to Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC)

military hospitals. Previously staffed exclusively by army nurses and orderlies

from the RAMC, the scheme introduced VADs to military hospitals. The VADs were

posted by the Joint Committee of the British Red Cross Society and the Order of

St John at Devonshire House. Special Service VADs were also sent to Red Cross

hospitals, both in England and abroad. After the first few months, the general

rule was that nurses were only sent abroad after they had served for at least

two months under the Joint War Committee in an auxiliary hospital at home and

had received a favourable report. The quality of care by the Red Cross meant

that every nurse employed to carry out work in a hospital overseas came up to

the standard of a sister, staff nurse or even a matron in an average London

hospital.

Nurses who wanted to be appointed completed an application form and would then appear before the selection board. After an interview, references were followed up. When applying to full-time nursing positions there were several rules for potential candidates:

They had to

have a certificate with three years of training in a general hospital of at

least 50 beds and a recommendation from the matron. Nurses with only two years’

training could work as staff nurses and be paid £40 per year. Where health

certificates and references were satisfactory, candidates were put on the lists

for Home or Foreign Service. A good knowledge of French was desirable for

Foreign Service. All nurses had to be equally willing to perform night or day

duty at home or abroad.

Candidates were

required to sign an agreement to serve in a home hospital for a period of six

months at a salary of one guinea per week. Insurance, outdoor uniform,

travelling expenses from London, board and lodgings were provided. Laundry cost

2s. 6d. per week, and lodgings at a hostel were provided between engagements.

Indoor uniforms

had to be provided by the nurses.

On and after 7

June 1917, third-class railway fares to London were paid to nurses on their

engagement and their fare home was paid on completion of their contract.

After one

year’s service with the Joint War Committee, the rate of pay was automatically

increased by 16s. 8d. per month. This took effect from 1 July 1917 and applied

to all nurses on the payroll on 30 June 1916.

Delia Page-Turner and colleagues Le Touquet 1917

The annual

holiday was two weeks per year, exclusive of days spent travelling and sick

leave. If a woman had to travel to her training, her travelling expenses were 18

shillings per week. If she stayed in nurses’ accommodation she was told to

bring the following (all marked with her name): One canvas or calico bag – six

feet four inches by three feet – to be filled with straw at camp One pillow or

pillow bag Two blankets One Macintosh rug is useful One enamel washing basin

and a piece of soap Two towels; one should be large for bathing One duster One

knife, fork and spoon One enamel cup and saucer Two enamel plates Two tea

cloths One brush for boots (1d nail brush will do) A bicycle lamp or a candle

lantern Small luxuries like: A deckchair Air cushion Spirit lamp Probationary

nurses were trained in nursing and first aid by Red Cross-approved medical

practitioners. Classes and examinations were arranged locally by divisions

until July 1916 when they were held at the College of Ambulance, 3, Vere

Street, under an agreement with the owner, Sir James Cantlie. The fee to be

examined was 1s 6d for evening candidates and 2s for day candidates. Two Red

Cross Officers supervised the examinations. Tredegar House, No. 99, Bow Road

was the London hospital’s training home for probationers before they were

admitted to the wards of the hospitals themselves. Members had to stay at

Tredegar House for seven weeks where they received instruction, board and

lodging and half a crown a week for washing, but no other pay. They were

examined in the sixth week. After passing the exams and receiving first aid and

home nursing certificates, they were sent for a month’s trial in a hospital. If

they passed the trial they were accepted into a hospital for “three months’

hard work” before they were accepted full-time.

In 1909 the

British Red Cross became involved in the VAD scheme. It was decided that

volunteers should wear an official uniform to reflect this role. In 1911 a

uniform sub-committee recommended the adoption of a standard uniform ‘having

regard to economy, utility and the practical duties the Red Cross detachment

would be required to perform on mobilisation’.

The Red Cross

women’s VAD nursing members’ uniform was described as: A blue dress of

specified material (red canton for commandants, blue lustre for members) to be

in one length from throat to ankle, and sufficiently full to be worn, when

necessary, over ordinary dress. To be buttoned in front under a two-inch box

pleat, slightly gathered in front at the shoulder and neck and finished with a one-inch-wide

neckband on which to fasten the white collar. The bottom of the skirt to have a

two-inch hem and two one-inch tucks. The sleeves (commandant) to be a small

bishop shape with a three-inch wristband and fastening with two buttons. The

sleeves (member) shall not come below the elbow. Ground clearance (pre-1917)

four inches; (1917–1930) six inches.

A starched

“Sister Dora” cap is worn across the head.

1911–1915:

“Sister Dora” pattern in one piece, having a three-inch hem to turn over in

front, which is square, the other part being rounded, having a narrow hem and a

flat tape stitched round from hem, and 12 inches in from the edge, through

which a narrow tape is run for drawing up.

1915–1930: an

oblong of white cambric or linen, unstarched, in two sizes, 28 inches by 19

inches, or 27 inches by 19 inches, hemstitched all round two inches from edge,

placed centrally on the head, the front edge to be worn straight cross the

forehead and the two corners of front edge brought straight round the head

fastening at the back with plain safety pin over the folds. The Red Cross

emblem at the centre front was introduced in c1925 Stiff, white, stand-up

shaped, linen collar of the improved “Sister Victoria” pattern, fastened by one

or two white studs or a soft turned-down collar of white linen that may be worn

with the working dress and fastened with a safety pin brooch bearing the

Society’s emblem, viz. a shield with a red cross on white ground. For the

nurses, white linen oversleeves, 15 inches long, fastening at the cuff with one

button and with elastic at the elbow. For the commandant, stiff white linen

oversleeves, fastened with one white stud. A white apron with the Red Cross

emblem is displayed on the bib. Made of linen, with bib pleated in band and

continuing in straps (without join), cut in three widths and pleated in band at

sides. On both sides is a large square pocket stitched on, the front part of

pocket having a narrow strip continuing upward and stitched in the two-inch waistband,

fastening at the back with linen button, the straps crossing over and also

buttoning about five inches from either side of centre at the back. The Red

Cross of Turkey twill, 4 inches in height and length, and of the authorised

Geneva pattern, with each limb 1-inch square to be sewn on the centre of the bib,

the bottom of the apron being finished with a two-inch hem. Length to be the

same as overall. A starched white linen belt, two and a half inches wide,

starched, to be worn over an apron. Ordinary black boots with black stockings.

Estimates for uniform material were requested from well-known firms and one was

selected based on quality and prices. A permit was obtained from the War Office

for the cloth to be purchased and an application had to be made to the

controller of woollen and textile fabrics at Bradford. They allowed the

selected firm a certain amount of cloth per week for making nurses’ uniform

coats. When coats and hats were received from Home or Foreign Service they were

inspected and if they were considered to be satisfactory, they would be cleaned

and relined for re-use which saved hundreds of pounds.

Competitions

were regularly held during the war to test the VADs’ knowledge of nursing

standards. The competitions were used to highlight the expertise of VADs and

encourage funding from local residents. The competitions included tests in

first aid and home nursing for women first aid in the field and stretcher

drills for men. A number of questions were also asked in order to test VADs. At

Huntingdonshire in 1914 the following questions were asked: What are bedsores?

What precautions would you take to prevent their occurrence, and if they occur,

how would you treat them? How would you prepare a patient and a room for a

major operation? Write a brief history of a case of enteric fever during the

third week, giving a temperature chart How would you prepare a linseed meal

poultice, an ice poultice, and a mustard poultice? What are the indications for

their use? What do you mean by Crisis and Lysis? In what illnesses do they

respectively occur? How do you make peptonised beef tea?

Nurses were

rewarded for their efforts with bars or stripes to display on their uniforms.

One year’s war service was signified with a bar, two and a half inches long, of

red quarter-inch universal lace, to be worn horizontally on the left forearm of

the jacket only, three inches from the bottom of the cuff. Two- or three-years’

war service – for each successive year’s war service a further bar may be worn

a quarter of an inch below the last one. Four years’ war service – a bar, four

inches long, of blue and white half-inch herring-bone pattern braid, shall be

worn horizontally on the left forearm of the jacket, three inches from the bottom

of the cuff, and shall replace the war service bars previously awarded. VAD

military nursing member – members of detachments in possession of scarlet

efficiency stripes awarded for service in a military hospital, or blue

efficiency stripes awarded for service in a naval hospital, may wear the same

on the right sleeve below the shoulder on the indoor uniform. Nursing members

appointed to the grade of assistant nurse in a military hospital or naval

hospital will wear the letters “A.N.” on the apron on the right side of their

outdoor uniform coats. Assistant nurse – members of detachments who have

qualified under the Society’s rules for the position of assistant nurse are

permitted to wear a blue stripe on the right sleeve below the shoulder in

addition to the war service stripes worn on the left sleeve on the indoor and

outdoor uniform. The letter “A” in gilding metal shall be worn on the bib of

the apron, a quarter of an inch above the Red Cross in the centre.

After the War had finished Delia Page-Turner returned to England back to normal life and in her case, she spent the season with her younger sister Bobbie Page-Turner in London.

The social season, or season refers to the traditional annual period in the spring and summer when it is customary for members of the social elite of British society to hold balls, dinner parties and charity events.

Until the First World War, it was also the appropriate time to reside in the city

(generally meaning London) rather than in the country in order to

attend such events developing friendships.

Delia met

H.S.H. Prince George Imeretinsky and became engaged to him in (Nov. 1920). George Imeretinsky was educated at Lancing

College not far from Brighton where Delia Page -Turner grew up.

Prince

George G. Imeretinsky (1897–1972) was a Georgian royal prince (batonishvili) of the royal Bagrationi dynasty of Imereti.

George was

born to Prince George Imeretinsky at Tsarskoye Selo, Saint Petersburg on 16 May 1897. George was

the godson of the last Emperor Nicholas II of Russia.

George was educated at Lancing College.

In 1916 he was granted an honorary commission in the 1st Battalion, Grenadier Guards, at the request of the Russian Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna. Holding the rank of lieutenant he was wounded in the Battle of the Somme in 1917 and served with the regiment until 1920.

Later he was an officer in the Royal Air Force, a Cresta champion, and was well known in Bentley racing circles, being a correspondent to various motoring journals. He married first in 1925 Avril Joy Mullens and divorced in 1932. She later married Ernest Simpson, the former husband of Wallis Simpson. Imeretinsky married secondly in 1933 Margeret Venetia Nancy Strong. His two younger brothers, Mikheil and Constantine were also educated at Lancing and joined the Royal Flying Corps. Prince George died in Cheltenham on 24 March 1972.

After

Prince George (1897–1972) the headship of the House of Bagrationi-Imereti was transmitted to his young brother Prince Constantine (1898–1978).

Their engagement

came to an end sometime in 1923/24 with George Imeretinsky marrying in 1925.

Delia Clive became engaged to Major John

Clive in August 1929.

John McClintock

Clive Birth 1891 - Florence, Italy Death Sep 1955 – died Cirencester,

Gloucestershire, England Mother Ellen Lizzie Lugard Father Henry Somerset-Clive.

Commissioned into the Army. 20/7/1920

(31/7/1920). Married Delia Page-Turner in 1921 Maj. 20/7/1934. Supply. List 13/8/1930.

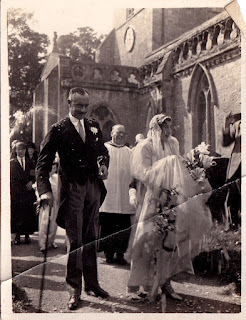

John Clive and Delia (Page-Turner) leaving Bicester Church at their marriage

FA Page-Turner to left 1929

- 14

April 1929 C. in C's Camp, India (Khyber). Regarding the future prospects

for Captain Clive of the 47th.Sikhs.

- a. 28 May 1929 Simla. Further on Clive's future: the possibility of Military Accounts Department. Mentions getting Contract Budget out of Finance Department, and benefit to the army in being prepared for war. Comments on the attitude of politicians and Swarajists. Comments Afghan situation.

Prince Edward spent four months in

India, travelling from Bombay to Calcutta and then from Madras to Karachi. As the

British Empire's Ambassador, the Prince visited India on behalf of his father

King George V, to thank the nation for the essential role it had played during

the First World War. October 1921-January 2022.

Major John Clive and Delia Clive were caught up in

the Quetta Earthquake, Delia recounted being pulled out of the rubble of her

destroyed living quarters while still in her night clothes.

An earthquake occurred on 31 May 1935 between 2:30 am

and 3:40 am at Quetta, Baluchistan Agency (now

part of Pakistan), close to the border with

southern Afghanistan. The earthquake had a magnitude of 7.7

Mw and anywhere between 30,000 and 60,000 people died from the

impact. It was recorded as the deadliest earthquake to strike South Asia until 2005. The quake was centred 4 km

south-west of Ali Jaan, Balochistan, British

India.

Movement on

the Ghazaband Fault resulted in an earthquake early in the morning on 31

May 1935 estimated anywhere between the hours of 2:33 am and

3:40 am which lasted for three minutes with continuous aftershocks. Although there were no instruments good enough to precisely measure

the magnitude of the earthquake, modern estimates cite the magnitude as being a

minimum of 7.7 Mw and previous estimates of 8.1 Mw are

now regarded as an overestimate. The epicentre of the quake was established to

be 4-kilometres southwest of the town of Ali Jaan in Balochistan, some 153 kilometres away from Quetta in British

India. The earthquake caused destruction in almost all the towns close to

Quetta, including the city itself, and tremors were felt as far as Agra, now in India. The largest aftershock was

later measured at 5.8 Mw occurring on 2 June 1935. The

aftershock, however, did not cause any damage in Quetta, but the towns of Mastung, Maguchar and Kalat were seriously affected.

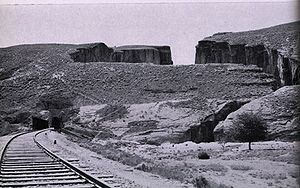

The Chappar

Rift in Balochistan, a landmark railway site, was affected by the 1935

earthquake when the mountains opened up in parts. The gorges and rifts owe much

to this earthquake for their appearance

Most of the

reported casualties occurred in the city of Quetta. Initial communiqué drafts issued by the government estimated a total of 25,000 people

buried under the rubble, 10,000 survivors and 4,000 injured. The city was badly

damaged and was immediately prepared to be sealed under military guard with

medical advice. All the villages between Quetta and Kalat were destroyed,

and the British feared casualties would be higher in surrounding towns; it was

later estimated to be nowhere close to the damage caused in Quetta.

Bruce Street immediately after the earthquake

The infrastructure was severely damaged. The railway area was destroyed and all the houses were razed to the ground with the exception of the Government House which stood in ruins. A quarter of the Cantonment area was destroyed, with military equipment and the Royal Air Force garrison suffering serious damage. It was reported that only 6 out of the 27 machines worked after the initial seismic activity. A Regimental Journal for the 1st Battalion of the Queen's Royal Regiment based in Quetta issued in November 1935 stated.

A destroyed Bungalow and Shop

It is not possible to describe the state of the city when the battalion

first saw it. It was razed to the ground. Corpses were lying everywhere in the

hot sun and every available vehicle in Quetta was being used for the

transportation of injured ... Companies were given areas in which to

clear the dead and injured. Battalion Headquarters were established at the

Residency. Hardly had we commenced our work than we were called upon to supply

a party of fifty men, which were later increased to a hundred, to dig graves in

the cemetery.

Rescue efforts

Tremendous

losses were incurred on the city in the days following the event, with many

people buried beneath the debris still alive. British Army regiments were among

those assisting in rescue efforts. Lance-Sergeant Alfred

Lungley of the 24th Mountain

Brigade, Naik Nandlal Thapa, and Lance Naik Chitrabahadur

Gurung earned the Empire Gallantry Medal for highest gallantry in these rescue efforts. In total,

eight Albert

Medals, nine Empire

Gallantry Medals and five British

Empire Medals for Meritorious Service

were awarded for the rescue effort, most to British and Indian soldiers.

The weather

did not help, and the scorching summer heat made matters worse. Bodies of

European and Anglo-Indians were recovered and buried in a British cemetery where soldiers had

dug trenches. Padres performed the burial service in haste, with soldiers

quickly covering the graves. Others were removed in the same way and taken

to a nearby shamshāngāht for their remains to be cremated.

While the

soldiers excavated through the debris for a sign of life, the Government sent

the Quetta administration instructions to build a tent city to

house the homeless survivors and to provide shelter for their rescuers. A fresh

supply of medicated pads was brought for the soldiers to wear over their mouths

while they dug for bodies in fears of a spread of disease from the dead bodies buried underneath.

The natural disaster ranks

as the 23rd

most deadly earthquake worldwide to date. In the

aftermath of the 2005 Kashmir

earthquake, the Director General for the Meteorological

Department at Islamabad, Chaudhry Qamaruzaman,

cited the earthquake as being amongst the four deadliest earthquakes the South

Asian region has seen; the others being the Kashmir earthquake in 2005, 1945

Balochistan earthquake and Kangra earthquake in

1905.

Watch footage of the

aftermath of the Quetta Earthquake:

https://player.bfi.org.uk/free/film/watch-quetta-earthquake-may-31st-1935-1935-online

Quetta is nearly six thousand feet above sea level and bitterly cold in winter. The train journey from Karachi involved crossing the Sind Desert and climbing the famous Bolan Pass which had tested the old Queen’s Royals so hard almost a hundred years previously at the beginning of the First Afghan War. The Battalion was now part of a large garrison comprising every branch of the British and Indian Armies and a large RAF detachment. Mess staffs set about making the somewhat barren messes and canteen more homely. There were numerous football and hockey grounds and the battalion football eleven soon made a name for itself by winning the Baluchistan District Championship. The polo club set about acquiring new ponies. With spring came the fruit blossom for which the area was well known, and things looked much more cheerful.

On 31st May 1935

at 3.40 am in the early morning, the city of Quetta and the countryside for 100

miles to the south-west including the town of Khelat were devastated by a

severe earthquake which lasted three minutes. There was another severe shock on

2nd June.

An official Government

communique issued on that day from Simla stated:

“1. The whole city of Quetta is

destroyed and being sealed under military guard from 2nd June

with medical advice. It is estimated that 20,000 corpses remain buried under

the debris. There is no hope of rescuing any more persons alive. The corpses

extracted and buried number several thousand. There are about 10,000 Indian

survivors including 4,000 injured.

2. All houses in the civil area

are razed to the ground except Government House, which is partially standing

but in ruins. The church and club are both in ruins, also the Murree Brewery.

3. One quarter of the cantonment

area is destroyed, the remaining three quarters slightly damaged, but

inhabitable. Most of the damage was done in the RAF area where the barracks

were destroyed, and only six out of the twenty-seven machines are serviceable.

4. The railway area is

destroyed.

5. Hanna Road and the Staff

College are undamaged.

6. Surrounding villages are

destroyed with, it is feared, very heavy casualties. The number is not yet

ascertainable. Military parties are being sent out to investigate and render

help.

7. Outlying districts, as

already reported from Khelat and Mastung, are reported to have been razed to

the ground with heavy casualties. All the villages between Quetta and Khelat

are also reported to have been destroyed”.

There follows a description of the first three days taken from the Regimental Journal of November 1935:

“It is not possible to describe

the state of the city when the battalion first saw it. It was completely razed

to the ground. Corpses were lying everywhere in the hot sun and every available

vehicle in Quetta was being used for the transportation of injured.

The area allotted to the

battalion was the Civil Lines, which included the Residency, the post office,

the civil hospital and the western end of the city. Companies were given areas

in which to clear the dead and injured. Battalion Headquarters were established

at the Residency. Hardly had we commenced our work than we were called upon to

supply a party of fifty men, which were later increased to a hundred, to dig

graves in the cemetery.

The system was to search methodically from house to house looking for the injured and the dead. The injured were removed to the hospitals and the dead were laid out on the side of the road and collected in A.T. carts.

Europeans and Anglo-Indians,

some unidentified, were taken to the British cemetery, put into trenches dug by

our men, and covered over quickly whilst the Padre read the Burial Service.

Indians were removed in the same way and taken to a burial ground outside

Quetta. Rescue work went on steadily throughout the day. At 8 pm we stopped. It

was impossible to dig in the dark and there were no lights; furthermore, the

men were exhausted, added to which they had had practically nothing to eat.

The next day, The Glorious First

of June - the Battalion marched at daybreak to the city. That was to be our

area for the day. It seemed a hopeless task - nothing but a pile of bricks.

Dead were lying everywhere. Squatting all over the place were survivors, each

in turn begging us to search this and that house for their relatives and

belongings. But we had all learnt a lesson from the previous day. No longer

were we going to dig for dead under the houses, but only for the living. The

previous day much precious time had been wasted by digging for dead and carting

them away. This time we were going to look for the living and leave the dead.

This was easier said than done, for in looking for the living we came across

the dead; they had to be buried at once, for already the city was beginning to

smell terribly.

Owing to the narrow streets

being full of bricks and rubble it was impossible to get ambulances up, and the

men had long journeys carrying the injured over piles of bricks to the nearest

point where ambulances could collect.

Long before the evening the men

were deadbeat. It was a very hot day, the digging and burying had been

terrific and the smell was hourly becoming worse. The pitiful requests of the

survivors - who would do nothing to help themselves - and the sight of the dead

bodies added to the strain. There was still a party at the cemetery burying

Christians - Mohammedans were taken out to their burial place by cart and the

Hindus burned their dead at any convenient place.

On the third day the Battalion

continued working in the city. In the morning we were still digging out live

people but they were fewer than before. The men had to work with medicated pads

over their mouths and noses owing to the danger of disease from dead bodies.

The chief job, however, was moving the survivors from the city. A big refugee

camp had been opened up for them on the racecourse, tentage was supplied and

water and food provided. Families were put into lorries by the men -whether

they liked it or not - and taken to the racecourse.

|

|

|

|

Racecourse Buildings.

By the evening it was apparent

that even if anyone was still alive they would never be found. Practically

every survivor had been evacuated to the refugee camp and the city was empty

except for military patrols. In the morning one party from the West Yorkshire

Regiment heard faint cries and dug furiously for hours. At last they came to an

opening and looked in - to find a cat and five kittens.

Not the least of our troubles

was the question of what to do with the animals. The city was full of cows and water

buffaloes, and most of them had calves. The injured were shot on the spot,

which only added to the smell.

On 3rd June -

that is to say the fourth day - the city was sealed. By that, it meant that no

one was allowed in the city, except on duty. A cordon of soldiers surrounded

the area, and for the next two days patrols were sent through the city clearing

out anyone seen and shooting stray animals. Since then the city has been closed

by barbed wire entanglements, patrolled day and night by soldiers at first, and

now by the North West Frontier Police.

During the first day or two,

when everything was disorganised, the riff-raff in the neighbourhood, and from

as far as forty miles away, came to Quetta. They knew that beneath all those

bricks thousands and thousands of rupees and valuables were buried; for

although a few shopkeepers put their money in the bank the large majority kept

it in a box under the bed.

Martial law was declared, which

meant looters could be shot on sight, and the 16th Cavalry were

posted on the outskirts of Quetta to stop them coming in, but it was quite

impossible to prevent them all and very often tribesmen were caught looting.

They were tied to railings in the most uncomfortable position possible. There

they were left in the hot sun all day, and in the evening given twelve across

the behind and released. It was quite an unpleasant punishment.”

There was still much to do. By

12th June all British women and children were evacuated besides

thousands of refugees and over ten thousand injured, some by air but nearly all

over the single railway line. Rations had to be provided for everyone, British

and Indian, and thousands of horses and mules had to be foraged. Tents arrived

from all over India and had to be put up, barbed wire fences had to be erected

around valuable stores and ammunition, refugees had to be controlled and

prevented from getting out of hand. Later, Wana huts had to be built and the

remaining barracks made more earthquake proof.

The Battalion subsequently

received a certificate from the Viceroy of India recording the thanks of the

Government of India for their share in the work of rescue and succour “which

saved so many lives and mitigated so much suffering”, and two soldiers of the

battalion, Lance Corporal G. Henshaw and Private A. Brook were awarded the

Empire Gallantry Medal which was later converted to the George Cross by command

of King George VI.

Work on reconstruction continued

almost continuously into the autumn. Conditions gradually settled down and a

pleasant break was provided during the winter for all ranks by a month’s

holiday in Karachi where the comparative civilisation, the warm weather and the

bathing, sailing and fishing were much enjoyed.

In 1936 the battalion reverted

to normal training, and in October they moved to Allahabad. The Regimental

History records that “They were especially sorry to leave the Indian battalions

of the brigade, the 2/11th Sikhs and the 5th/11th Sikhs and Duke of Connaught's Own, 4/19th Hyderabad

Regiment and the 2/8th Gurkha Rifles, who had filled them with

great respect for the Indian Army.”

Major John Clive, MC, Changi

Prison Prisoner of War

Following the Fall of

Singapore on 15th February 1942 the Allied soldiers including the Commonwealth

forces and the Indian Army were moved to Changi prison. Major John Clive was

one of over 80,000 who surrendered to the imperial Japanese army. The Prisoners remained there until they were liberated

by troops of the 5th Indian Division on 5 September 1945 and

within a week troops were being repatriated. The conditions were a lot better

than many Japanese POW camps but the conditions did take their toll. Major John

Clive died prematurely in 1955 aged 64.

A large prison camp complex opened by the Japanese during World

War II to house POWs captured in Singapore, Changi was set on nearly 16 square kilometres

of undulating hills at the eastern end of Singapore.

After the island's fall on 15 February 1942, over 15,000

Australian and 35,000 British prisoners were herded into Changi Prison,

formerly the magnificent Selarang Barracks and, lately, home to the Gordon

Highlanders, a Scottish regiment. Now Changi was supposedly a hospital centre,

but in fact, it served as a massive POW camp. The barracks were badly damaged

by shelling.

As more and more prisoners filed into Changi, overcrowding

became an ongoing problem. Within two months, 8,000 prisoners were without

shelter. There was no water, lighting, or sewage facilities and clouds of flies

were a constant annoyance. Food stores rapidly diminished, and the men were

placed on strict rations.

There was only a nominal Japanese presence inside the vast

compound, the guards mostly staying outside the confines of the camp. Changi's

administrative staff had warned the prisoners that, apart from a rice ration,

they had to be self-supporting, so the prisoners were placed under the

management of their own senior officers. The officers encouraged the men to

clear drains to prevent the breeding of malaria-bearing mosquitoes, and they

supervised efforts to dig latrines, scrounge for food, and get wood for cooking

fires.

Army engineers repaired the shattered plumbing and restored

electricity. Lieutenant-Colonel Glyn White of the Australian Army Medical Corps

smuggled in hospital equipment, drugs, and medicines, and soon the camp was

functioning reasonably well. Gardens provided fresh food, and eventually, 10

truckloads of green vegetables were being harvested every week. A poultry farm

was established as well and fresh eggs were distributed under the direction of

doctors.

With the camp running smoothly, the men looked for other

diversions. They attended lectures on a variety of subjects, studying such

things as history, geography, engineering, and business. Major John Clive wrote

a Dictionary in three languages, English French and Italian. An Australian

concert party was formed, and well-attended shows (which continued until July

1945) gave the men some relief from the boredom and uncertainty of prison life.

During one early show, an Australian comedian named Harry Smith coined a

melancholy slogan that will forever be associated with Changi: "You'll

never get off the island!"

The Japanese soon began drawing on their prisoner population for

local work parties, and over 8,000 men laboured on tasks such as filling bomb

craters and gathering scrap metal for export to Japan. In May 1942, around

3,000 prisoners known as A Force were taken out of Changi to work on the

Burma-Thailand Railway. Two months later, a further 1,500 were shipped to

Sandakan in British North Borneo to begin work on an airfield, while others

went to labour camps in Japan. In August, the Japanese removed all the camp's

senior officers above the rank of lieutenant colonel and shipped them to

Formosa.

As prisoner numbers dwindled, the entire camp, including the hospital, was moved to Selarang. Conditions there worsened dramatically and by war's end, Changi's POWs were in a pitiful state, diseased, starved, their bodies reduced to skin and bone. Today the Selarang Barracks still stands, while Changi itself is now home to Singapore's huge, modern international airport.

Delia and John Clive settled into life at Coln St Aldwyns in the Cotswolds where John died in 1955 and Delia died in 1976.

%20leaving%20Bicester%20Church%20aftr%20their%20marriage%20FA%20Page-Turner%20to%20left.jpg)

%20and%20her%20husband%20John%20Clive%20leaving%20Bicester%20Church%20after%20their%20wedding%20service.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment

Please leave any interesting factual comments relating to the post(s)