Frederic Ambrose Wilford Blaydes (Page-Turner) Born 30th July 1882 – 7th July 1936, biography and Life as a district officer In Sarawak, under the Rajah Brookes

Frederic Ambrose Wilford Blaydes (Page-Turner)

Born 30th July 1882 – 7th July 1936,

Born at Tilsworth Vicarage and baptized on the 10th September at Tilsworth church.

Pupil of Hincwick House School under William Augustus Orlebar. He attended Berkhampstead Grammar School, confirmed at the school chapel on 16th December 1897 by the Bishop of Colchester. He left Berkhamstead Grammar School in 1900 and entered the National & Provincial Bank of England for a year. In 1902 he received an appointment under Rajah Charles Brooke, he sailed for Sarawak on 13th Feb 1902 and served there until 1930. He "married" a Malaysian Woman of high standing in 1904 and had a son, Samuel (Sammie) Blaydes in 1905.

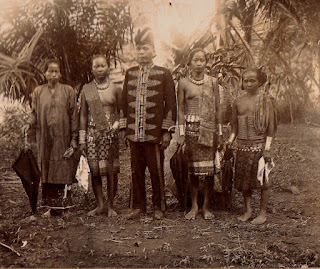

Samuel (Sammie) Ambrose Blaydes 1905-1967 seated 2nd from left

first son of FAW P-T Sarawak

In late1930 after 28 years of service to the Brooke dynasty and Sarawak he returned to England to inherit the Ambrosden estate in Oxfordshire from his late brother Hugh Gregory (Blaydes) Page-Turner.

F A W Page-Turner on his Hunter "Flash" Ambrosden Park 1933

He Married Peggy 8th June 1931 at St Mary Abbots Church Kensington London and they lived at Ambrosden House, St. George's Avenue, Weybridge, and Ambrosden House Bicester, Oxfordshire, and Sundon, Bedfordshire, (1882-1936), was the father of the Rev. Edward Gregory Ambrose Wilford Page-Turner, (b.1931), and Noel Frederick Augustus Page-Tuner (b.1932)

Arms: Quarterly, 1 and 4, Quarterly, i and iv, Argent a fer-de-moline pierced Sable (Turner); ii and iii, Azure a fess indented between three martlets Or (Page); 2 and 3, Vert on a saltire between four pheons Argent a pomeis on a chief engrailed Or a lion passant Gules (Blaydes). Crest: A lion passant guard.

F A W Page-Turner Service in Sarawak 1902-1930

Explanation of colour coding headings:

Timeline

and key dates for FAW (Blaydes) Page-Turner’s service in Sarawak in green

Timeline and key dates for Sarawak History in blue

Service in Sarawak 1902-1929 & 1930 (returned after retirement)

F A

W (Blaydes) Page-Turner March 23rd,

1902 to 26th March 1903: appointed

Cadet Baram, Bintulu

Bintulu is a coastal town on the island of Borneo in

the central region of Sarawak, Malaysia. Bintulu

is located 610 kilometres (380 miles) northeast of Kuching, 216

kilometres (134 miles) northeast of Sibu, and 200 kilometres (120

miles) southwest of Miri, Bintulu

is the capital of the Bintulu District of

the Bintulu Division of Sarawak, Malaysia.

James Brooke was appointed the White Rajah of

Sarawak (now known as Kuching) by

the Bruneian Empire in 1841. In 1861, the Sultanate of Brunei

ceded the Bintulu region to Brooke. Bintulu was a small settlement at that

time. A wooden fort named Fort Keppel was built in the village, named

after Sir Henry Keppel, who was a close friend of the Rajah James

and Charles Brooke. Sir Henry Keppel was responsible for crushing

the Dayak piracy in the Saribas between

1840 and 1850.

The fort of Bintulu which was built entirely of

wood, was in somewhat ruinous condition. It stood nearly on the seashore, and

just behind it, at a distance of few paces, the primeval forests

commenced...Some China men had settled at the vicinity of the fort and had

built a small bazaar, but the houses of the Melanau chiefly form the

village beyond the Chinese kampong (village). These Melanaus used to live

further up the river, but since the construction of the fort, and the

installation of an officer of the Rajah near the mouth of the river, they came

to settle near the sea – a thing they would never have dared to do in

former days for fear of the attacks of the Lanun pirates and Dayak pirates. — Reported

by Odoardo

Beccari in 1904

Bintul was one of the most isolated places in Sarawak. Only one officer looked after the district. The nearest station was Mukah, 75 miles along the coast, and the closest medical assistance was at Kuching or Labuan, both 250 miles away, with no means of communication if help had been needed. To make matters worse, from November to March the northeast monsoon pounded the river bar into such fury of surf that no vessel could safely navigate the waters. The duties of a cadet, although dealing mainly with minor tasks, were multifarious and did not lack variety. One former Brooke officer recalled that a Cadet was left to do the mundane duties, which the Assistant Resident had “no time or desire to do” The Cadet had to take charge of the Rangers and was responsible for managing prisons. He was directed to dispense medicines, sell postage stamps, and observe his superiors in their work. The fort was more comfortable than most. The Ranger guard occupied the ground floor. The Courtroom and the Acting residents & Cadets quarters comprised the first floor. From the windows was a grand view of the sea. All the men of Bintulu were sailors and fishermen. The officer and Cadet dined on fresh fish every day. Custom had it that when the fishermen returned in the evenings, they should throw some of their catch onto the fort landing stage for the use of the staff of the garrison.

Legal duties consumed a greater part of the Resident’s work. The Resident was regarded as the chief Judicial officer in his Division or district and used the British concept of Justice. The Resident was largely left to exercise his discretion over legal matters. Each Resident maintained a Divisional Council, attended by local chiefs. These chiefs were appointed by the Government, which almost invariably chose the accepted head of the tribes. Each village, whether Malay, Melanau , Land Dyak, Sea Dyak or Kayan, had its hereditary or elected head, who were responsible for maintaining order and paying taxes. Forts were built to the same design so that they were uniform. Square stockades with watch towers at each corner, made of planks of ironwood, which no native missile can penetrate. The fort was the focal point of administration and it attracted traders. Chinese bazaars and Malay Kampongs grew within the vicinity of the fort. The success of a Resident depended on his acquiring intimate knowledge of the local inhabitants.

Each Division was under the Resident who in turn supervised the work of Assistant Residents, Cadets, and Malay Native Officers appointed by the Rajah but deriving much of their authority by virtue of their descent from the datus. Native officers assisted the Residents in general administration. In addition, there were the para-military Sarawak Rangers (mostly Iban) and police (mostly Malay), and a number of Malay , Chinese, and Iban Clerks.

Recruitment for the Sarawak service was conducted largely based

on family connections and personal recommendations from retired officers. Frederic Ambrose Page-Turner’s sister Dorothy

was the wife of Hanbury Lewis Kekewich from Peamore Estate Exminster Devon and would have known the

Brooke family at Sheepstor Dartmoor only 1 hour away in Devon. The Page-Turners

of Ambrosden Bicester were also 1 hour

away from Cirencester where Rajah Charles Brooke spent many months of the year

in his later life.

A Newly appointed Cadet was allowed £40 for his passage from

Britain to Sarawak. The 1873 Order provided leave of two years on half pay for

officers with at least ten years’ service.

1917 Monthly salaries

Divisional Resident

$450

Second Class Resident $300

Asitant Reisdent $200

Cadet (Newly appointed) $120

The British officers were not regarded as common men, of

course; they were epic figures. Ibanized versions of their names appeared in

songs and stories, and are recalled to this day. Bailey was “ Tuan Bili”

Deshon ( a particularly hard name for

the Ibans to pronounce) was “Tuan

Lengsong”. Page-Turner a veteran of the second Division Resident under both Charles and Vyner Brooke, was “

Tuan S’tarna”

9th June 1902 Cholera Expedition (2000 men died initially and the outbreak affected the whole of Sarawak killing many of the Indigenous people but no Europeans)

19th June 1902 Pengarah Ringkai of Saribas died

FAW Blaydes took the Page-Turner name and coat of arms

in 1903 following his father (Frederick Augustus

Blaydes.) inherited the estate of his Uncle Sir Edward Henry Page-Turner, 6th Baronet, who died childless.

Sibu is a landlocked city located in the

central region of Sarawak,

Malaysia. It serves as the capital of Sibu District within Sibu Division and

is situated on the island of Borneo.

Covering an area of 129.5 square kilometres (50.0 sq mi), the

city is positioned at the confluence of the Rajang and Igan Rivers, approximately

60 kilometres from the South China Sea and

191.5 kilometres (119 mi) north-east of the state capital, Kuching. The

city's history dates back to its founding in 1862 by James Brooke, who

built a fort to protect against attacks by indigenous Dayak people.

Subsequently, a small group of Chinese Hokkien settlers established themselves

around the fort, engaging in various business activities. In 1901, Wong Nai Siong led

a significant migration of 1,118 Fuzhou Chinese from Fujian, China,

to Sibu. Over time, infrastructure development took place, including the

construction of the first hospital, Sibu bazaars, Methodist schools, and

churches.

There was no hard and fast rule on how an outstation

government should be run; the Residents themselves would determine the measures

most suitable according to local needs and demands. The principle of government

was thus to allow “system and legislation” to “ wait upon occasion” This type of government closely resembled an

ad hoc administration which reacted to a situation rather than anticipated

problems.

The Rajah impressed on his officers the importance of

treating the natives with respect and of soliciting the co-operation of local

chiefs. He also encouraged his officers to cultivate social and friendly

relations with the natives to familiarize themselves with local problems.

The Rajah preferred his recruits to be men with a personal touch, not brilliant scholars. He wanted his recruits to be in their early 20s and single. His officers were not permitted to marry until they had completed at least ten years of service. While the Rajah frowned on the presence of European wives, he did not discourage his officers from illicit liaisons with native women and Malys.

Charles Brooke, 2nd Rajah of Sarawak

In his book “ Ten Years in Sarawak” Charles Brooke

showed a predisposition to the idea of Miscegenation between Asians and

Europeans, which he believed suited tropical climes and the circumstances of

such Asian countries as Sarawak. Rajah Charles fathered in 1867 a son by a

local woman, the son was called Esca. This practice became a subject of

criticism from members of the Sarawak clergy.

As a District Officer, their duties varied widely. Tasks include

keeping proper documents, checking records, vaccinating the Dyaks, and seeing that

Law and Order were observed. He was a Judge, prosecutor, garrison commander,

chief medical officer, and office boy all at once. Helping and solving the

problems of the Dyaks. There was no telegraph, and few letters: orders came by

runner from Kuching; very infrequently the Rajah came on tour of inspection.

Dyak Headman & Dyak Women

Occasionally there were uprisings in the interior which had

to be put down. Large expeditions were planned and carried out. Led by European

officers hundreds of Dyaks , Rangers, and Malays. Days were spent marching

through jungles, navigating rivers in canoes, always on alert from hostile

tribes. The heat, mosquitoes deadly

swamps, leeches, and many other hazards such as floods, drought, cholera, and

the plague aggressively affected them.

Dyak or Ulu Warrior

The Rejang . the biggest river in Sarawak , had diverse

tribes living on its riverbank. In the upper waters were colonies of Kayans,

and bands of nomad hunters such as Punans, split into groups of Ukits and Lisums.

All these were the wild men of Borneo, wandering from place to place in the

thickness of the jungle, erecting flimsy shelters of palm leaves on sticks and

living entirely on wild produce vegetables, and animals. The Punans would hunt

with poisoned darts and blowpipes. A B

Ward describes an expedition in his book that he organized for action against

the Balleh Dyaks consisting of a force of 1200 Dyaks and 600 Malays , the

Balleh Dyaks had murdered 18 innocent people in the 3rd division and

then under the leadership of the swashbuckler named Tabor, had invaded the

second division and taken five heads in the upper Saribas. We had several

ex-soldier Dyaks to pick from being careful to divide the chosen men equally among

the various tribes to avoid jealousy. Fort Alice was thronged with young old

and decrepit warriors all hoping to be selected. Arms and ammunition had to be

checked, snider rifles were handed out and each man had a rope ring covered in

red cloth to wear around his head, it combined protection against a cutting

blow and a distinctive mark in a melee. In the middle of May, I had the whole

force on board the “Natuna” at Lingga and

we sailed straight away for Sibu. The 500-tonne ship was crammed with 2000

souls. We reached the rendezvous in Kapit,

the place was swarming with Dyaks, and over 10,000 men had turned out for the

Rajah’s cause. The Rajah himself was there in the “Zahora”. Six Europeans

accompanied the expedition and an instructor who commanded 100 Sarawak rangers

armed with a seven-pounder M L Gun.

HHY Zahora, Rajah Brooke's Yacht moored in front of the Astana

Kuching Sarawak

The prerogative of fighting for the Dyaks is a highly prized

privilege of the Batang Lupar and Rejang Dyaks, the majority went in their

boats armed with their weapons rationed themselves and received no pay. Under judicious supervision they were able to

appropriate any abandoned loot in the enemy’s country, this sometimes meant

quite a lucrative proposition. The Rajah

arranged his expeditions so that possible contact with the enemy would occur

about the time of the full moon. The expedition left passing the Rajah who

stood on the quarter deck of the “Zahora” where he doffed his Homburg hat to each

passing boat.

That night we were at Mujong mouth where the expedition

camped, some of the enemy scouts came too close and paid the ultimate price. On

again with the European boats leading the next day to keep order and

discipline. As the river narrowed the task was easier however there were new

tactics to contend with from the enemy. Mammoth trees had been felled across the

stream generally where a rapid made progress difficult. These barriers had to

be hewn apart by axes while a wary eye was necessary to forestall an ambush.

For a week we struggled up the Melinau, shallow from lack of rain; punting,

pulling, shoving the hundreds of boats over a succession of rapids; paddling where

the water lay deep enough over the pebble bed, boats were punctured and put out

of action. Occasionally there were skirmishes with some wounded as a result of

enemy encounters. The enemy eventually retired inland to Bukit Salong. We had

expected this move because the Balleh Dyaks always boasted the hill was impregnable.

The route was tricky with many obstacles to overcome eventually we came to a

halt at the foot of Salong Hill. From the summit, we could make out war cries, and

rocks were thrown down. I was surveying the position from the base when a

warning voice sang out. Looking up, I saw the whole hill tumbling down on top

of us. I stood transfixed for a second or two until my orderly grabbed me by

the arm and dragged me under the shelter of a rock. The rebels had cut the

trees loose at the top of the hill with the result that the whole jungle

hillside had crashed to the bottom. The rock saved our lives. In the morning a

hillock was cleared, the gun mounted the first few shells were wide and

greeted with derisive jeers from the top. Then the rangers got the range, the

shells burst over the ridge, and we could hear shouts of consternation this

time, at night there was wailing on the hill but no hint of surrender. The next

morning we essayed a shot, but now there was a deathly silence on Salong.

Scouts went ahead the hill was deserted, the property was scattered everywhere

and some dead bodies lay cold. Our task was accomplished.”

17th January 1904 Death of Admiral Keppel

29th March 1904 The Bong Kap Encounter, Kanowit immense

boat Bong Kap captured accommodated 100 paddlers. Rajah Mudah became the Resident of the 3rd

division

15th

August 1904 FAW Page-Turner posted to Simanggang

31st December 1904 Tama Bulan died

5th January 1905 Cession of Lawas

1st

July 1905 – 31st May 1906 assistant resident Simanggang 2nd

Division to A B Ward

F A W Page-Turner with Iban Warrior Guards 1919

FAW Page-Turner with fellow Brooke Officers Sarawak

The Second Division, as defined when constituted on 1st June 1873, extended from the Sadong River to the Rejang River (but not including either river). It was redefined 28th July 1885 as extending from Sadong River (exclusively) to Kalaka River (inclusively). Batang Lupar, Saribas and Kalaka rivers. It covered 6-7 thousand square miles with a population of 60,000 Dyaks. Three English officers controlled the whole of this territory.

No Resident was appointed in charge of the 2nd

Division until 1 Sept 1922. The reason was that the second Rajah, Tuan Muda, oversaw

the Division from his accession in 1868 until 1916 when he handed it (and the

Dayaks of the Third Division) over to the third Rajah, who was then the Rajah

Muda.

Following officers of the 2nd Division :

Cruickshank, James Brooke 1875

Brooke, Charles Rajah

1868-1916

Brooke, Charles Vyner

Rajah 1916-1922

Page-Turner, Frederic Ambrose Wilfred 1922-1930

Archer, John Beville 1930-1934

The settlement of Sri Aman was originally named Simanggang,

after the stream of the same name which drains into the Batang Lupar.

Simanggang was established in 1864 during the reign of Rajah James Brooke, but

it was not the original location of the government outstation. Rajah James

established a government outstation at at Nanga Skrang in 1849, but later

relocated it to Simanggang. The original Skrang outstation was established

after the Rajah, (with the help of the British Navy,) brutally ambushed a large

returning Iban/Malay maritime expedition at the Beting Maru sandbank, offshore

from the mouth of the Batang Lupar. This followed two equally brutal

expeditions in 1843 and 1844, where the Rajah was trying to put down Iban and

Malay resistance to his rule. He felt the fort and outstation would provide a

physical presence in the mostly Iban area to maintain his control. The fort was

constructed on the opposite side of the Batang Lupar from the original pasar

settlement there. The fort, (later known as Fort James,) was located across

from the mouth of the Batang Skrang in order to control the movement of Skrang

Iban groups, which had been resisting the rajah’s directives. The fort also had

to be able to withstand the attack of the rajah’s enemies, although it never

actually came under actual attack at that site. The establishment of the fort

and its European officer attracted the aristocratic abang abang from their

upriver kampung, and convinced the Teochiu Chinese traders to build five

shophouses there.4 Before this time, the area was not very secure due to

conflict between local groups.

Settlements were also prone to attack by Iranun raiders from what is now the Southern Philippines. For this reason, most settlements were located in defensive locations up rivers, rather than on the coast. In 1863, it was decided that the Skrang outstation be relocated to Simanggang, as the Skrang location was prone to seasonable flooding, not surprising in an area where padi paya was grown. In 1864, all of the inhabitants of the Skrang outstation moved to the new location at Simanggang. At that time, there were about 2,500 Malays and approximately 100 Chinese living at Skrang, in addition to the fortmen and their officers. There were no overland routes between Skrang and Simanggang, and the relocation was done entirely by boat. The fort building at Skrang was dismantled and transported downriver, and reassembled on a small hill on the Batang Lupar, downriver from Sungai Simanggang. The Malays established themselves in two locations: firstly, on the upriver side of the Simanggang River where there was a small hill, and secondly on the downriver side of the fort. The Chinese traders settled on the flat land between the Sungai Simanggang and the fort. The new outstation at Simanggang was based on the settlement pattern at Skrang, and became a prototype for other outstation settlements in Sarawak, with its three components of fort, Malay kampung and a pasar made up of Chinese shophouses, linearly arranged along the river. Almost all other outstations established during the Brooke period conform to this pattern, including Sibu, Kapit, Marudi, Kabong, Engkilili, Kanowit, Bintulu and Betong. These patterns can still be read through the urban morphology of those settlements, although in some cases (such as Betong) the relocation of the pasar and the change of the path of the river may confuse matters.

At Simanggang, the fort was remaned to ‘Fort Alice,’ and its functions began to change from surveillance and defence to more civil functions. While it still functioned as a military establishment (it housed the fortmen and their weapons,) its functions were expanded to include the court, treasury, dispensary, development office, post office amongst others.

The resident’s bungalow was where Charles Brooke had lived while he was Resident, and came to be known as the ‘Simanggang Astana’ when Charles Brooke became the second Rajah.

The Restored Residents Bungalow Simanggang now a

Museum & Government Guest House

FAW Page-Turner (seated second step down from the top)

& guests Simanggang

F A W Page-Turner sharing the Port & FAW Page-Turner with the Dutch Controleur seated for Sundowners at a Bungalow circa 1920'sShort Video of the Residents Bungalow today

The use of the term ‘Astana’ is significant, as the Brooke Government often used local terms to project authority. Charles’ son, Vyner, was also stationed at Simanggang before he became the third Rajah. The population of the Lupar Residency, which included all the rivers upriver from Simanggang, continued to grow slowly throughout the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. In 1871, the Lupar Residency had 35,492 inhabitants, whereas the ‘capital’ of the residency, Simanggang; had about 3,500.

Simanggang was one of the major towns in nineteenth century Sarawak. It was the centre of a significant rice producing area, and Sarawak’s development at that time also saw the area’s padi production increase - it provided padi to a lot of the state at that time. Development in the residency also came from the increasing cultivation of cash crops such as pepper and rubber, which brought a lot of wealth into the residency. Simanggang’s development cannot be seen in isolation, rather it must be seen as part of a larger area, and as the main centre of that area where agricultural produce from the hinterland was collected or cultivated to be on-sold to other places, and where imported agricultural and other goods were available for upriver groups to buy.

2nd January 1906 Brunei accepts a British

Resident

1st April 1906 Datu Bandar Haji Usop of Sibu died

Bung Muan Mountain Bau Sarawak

FAW

Page-Turner 5th July 1906 31st December 1907 Duty in

Rejang (Third Division) and moved to Kapit.

6th October 1906

Datu Bandar Haji Bua Hassan died

FAW

Page-Turner 1st Jan 1908 made

Resident 2nd Division

The Resident had to write regular reports mainly

concerning imports and exports of rice, the state of local finances, figures on

the economics of government, and precise statements on raids by head-hunters,

many of these reports appearing in the Sarawak Gazette. The Second Division in 1900 had the following

populations :

50,000 Ibans

10,000 Malays

2000 Chinese

FAW Page-Turner standing to the left behind the ships wheel

at the Jetty Kuching walking past the Customs House

The second division was not important to the economy, lacking good soil and mineral resources. Simanggang was not isolated in comparison to many Sarawak outstations, but the trip from Kuching still required two days by a combination of a Government steamer and a hand-paddled river boat. To survive a long assignment in such a place, an officer had to have greater than average inner resources. Residents were asked to take an interest in their surroundings.

Kuching Museum and Orchid House, Kuching

They were asked to collect specimens for the Sarawak

Museum, which the second Rajah founded. They were also encouraged to write

articles on local ethnography and folklore for the Sarawak Gazette. The

Resident was expected to speak Malay and Iban.

Hospital Simanggang

The Life of the British Officer resolved itself into a

routine. Daily Weekly and yearly events assumed the nature of minor rituals,

giving a regular rhythm to existence. Every day at Simanggang the Resident

presided over the law court and corresponded with his fellow Resident about

such problems as absconded Chinese coolies and wandering Ibans who had deserted

their families, whilst the most junior British assistant sold stamps and

dispensed harmless medication for two cents a dose. Every evening the officers

entertained each other at their quarters in Fort Alice, where all of them lived,

and sometimes spent long hours chatting with visiting Iban or Malay headmen.

Every night at eight o’clock the Iban Corporal of the guard raised the drawbridge over the

cheveaux-de-frise which surrounded the fort, to the following long-drawn chant

: (now just a ritual)

“Eight o’clock has sounded,

The bridge is raised,

The gate is locked

No one can come up anymore”.

Every Sunday the Junior officer inspected the Jail, the squad of Sarawak Rangers, and the few government buildings. Then the Resident and his men paid an official weekly visit to the Chinese bazaar, just down the grass-covered slope from Fort Alice.

The British Officers spent a great deal of time on tour. On their travels, they met local leaders, heard their news of other rivers in the Division, and collected tax receipts. Above all, they settled court cases, sometimes in the various other forts, but also frequently in boats, in the five-foot way of Chinese bazaars, and on the child and chicken-covered verandas of Iban longhouses.

Early each morning the Court Room began filling up with

Dyaks, Malays, and Chinese. At ten o'clock Police arranged wooden benches

before the court table The Resident and his assistant Resident would take up

their positions alongside the native officers behind a green baized table.

Cases were of all kinds, criminal and civil, the latter chiefly concerned

disputes over farming land or the division of inherited property. The two

protagonists occupied the front bench arguing their case in their own language.

The Resident did all the cross-examining, writing out a synopsis of the matter as

he proceeded, and if either of the parties wandered from the subject, he

received a dig in the ribs from the police behind. There were no lawyers to

complicate the point at issue; judgment was given and the litigants made way

for the next.

Among the cases sometimes brought up in court was the

inheritance of a “tajau”, an old jar. To look at they are nothing remarkable.

Brown glazed “Ali Baba Jars” some with a

dragon ornamentation some with a scroll, where they came from is a mystery

probably from China or Siam. The Dyak prized them as we do old paintings.

Chiefs and old Dyaks have rows of them in the family room. Jars would exchange

hands for over $1000 in the 1920’s.

Money was spent on jars or silver ornaments made for the women. Silver

dollars were melted down to fashion a belt or bracelet.

The Method of summonsing Dayaks to court was peculiar.

Paper documents would be useless, so a “tongkat” a Malacca cane walking stick

with a brass head and a government mark, was sent abroad from village to

village with verbal message until it reached the person named, who forthwith

hurried to Simanggang.

The Resident, FAW Page-Turner (seated Center) & his staff Fort Alice Simanggang

Detail, FAW Page-Turner the Resident seated center.

During a visit by Rajah Charles Brooke in 1899, the Rajah

settled 22 court cases at Fort Alice over three days; including nine lands

disputed, four divorces and desertion cases, three inheritance quarrels, one

application for a gun license, one application for a goldwork permit, one

dispute over a boat, one slander case. F.A.W. Page-Turner famously decided to

adopt a Chinese young girl to solve a custody case between estranged Chinese

parents. Gregory Page-Turner his grandson met this lady in the mind 1980s on

his first visit to Sarawak and Kuching. The lady was in her late 80’s living

with her prosperous children in Kuching.

Afternoon office work was a repetition of the morning

work but less exciting because there was no performance of the Law Court. After the heat of the afternoon lessened when

it was cool, the officers would take exercise. One would ride one of the two

government ponies the other officer would walk around the cowsheds or visit the

prisoner work gangs.

The Tidal Bore arriving just before Fort Alice Simanggang

In the evening with twilight, the officers would sit in the cool on a seat overlooking the river with refreshing drinks and watch the boats pass on the stream and the tidal bore. Scarcely an evening passed without a visit from various native Dayaks who would sit on the grass to tell the officers the news from upriver and beyond. Evenings were also spent reading books and newspapers.

On a typical tour, the officer first preceded from Simanggang to Betong, traveling up the Skrang River by boat, then over-land by trail. At Betong, on the Saribas, he lived in the dovecote-like attic above the main fort Lili, sweltering when the sun beat down on the ancient shingle roof. After a busy few days of hearing cases among the argumentative Saribas Ibans, he went downriver to Pusa, a low-lying mosquito-plagued Malay settlement. After finishing there he continued by river and sea to Kabong, built over mud flats at the mouth of the Krian, passing by the site of the 1849 Battle of Marau on the way. His final stop was an hour’s paddle up the Krian River at Saratok, again in Iban territory. The entire tour took as much as a month to complete, depending on the amount of work encountered. Expeditions were conducted in two long boats paddling upriver. At every turn wooded hills, crowned with Dyak Longhouses came into view.

Dyak Men with Brooke Government Officer

Dyak Girls in Costume

As these houses were passed the boat’s crew burst

into a yell fetching out scores of men, women, and children who ran down to the

bank shouting out invitations to stop.

Expeditions also visited gold mining settlements manned by Chinese

Sambas. When the rivers became shallow

bamboo poles were used to punt their way along the rivers. On these peace tours

upriver almost all Dyak houses were visited our reception was most cordial. We sat for hours in the “ruai” or public hall

of the houses surrounded by men, women, and children all bombarding us with

questions. Few of them had ever seen a white man before and the girls were

anxious to test the whiteness of our skins by wetting their fingers and rubbing

them on our calves to see if it was permanent, On these visits a quantity of

native spirits was brought out “tuak”. Although these Dyaks were opposed to the

government simply because they were not allowed full liberty to persist in headhunting,

they appeared to have a great reverence for the Rajah.

European Women visiting a Dyak Longhouse

For inland Dyaks the landing stage was normally a half-submerged tree trunk, slippery as a greased pole. Then for some way, the only path was over “batang” flimsy poles supported on cross sticks a foot or more above the black oozy swamp. A Dyak could trip along in perfect ease, his toes grasping the sticks, however, a European wearing shoes was seriously handicapped on these slippery rotten rolling “batang.” A narrow raised path extended for miles through virgin forest until it emerged onto hills green with “Lalang” grass. Here and there a scattered hut, standing alone on the banks of the Saribas River fort Lili.

Walkway over Swamp Betong to Dyak Longhouse

Shooting was a prime recreation during the winter months

when the northwest monsoon brought in snipe and often wild ducks. Snipe was

usually found in the vast buffalo swamps of Limbang and Trusan. Going upriver in

the launch parties would anchor off a well-known “Laman” and walk up the plain.

It was strenuous work in the broiling sun, up to one's knees, sometimes to

thighs in mud, with the cr-k-k-k of snipe getting up all around. Later in the

afternoon after a break to wash down and refreshments when the sun was sinking,

green pigeons would fly across the river. These shooting parties would span

from 2 to 4 days with a stay in Trusan.

When travelling from Kuching to Simanggang a small government steamer was normally the best means of transport. Out of the mouth of the Sarawak River, sweeping east passing the low-lying mangrove coast, passing the wide entrance to the Sadong River and the domed island of Burong where innumerable sea fowl made their homes undisturbed, except when startled into protesting clouds of white, grey and black. Ahead lay the large mouth of the Batang Lupar River with its protruding teeth, conical mounds, big and little Triso. Passing through and then entering the Simanggang district. In its lower reaches the Batang Lupar is 3-4 miles wide. After 15 miles a white fort emerges at Lingga where the travellers stay overnight before transferring to war boat canoes measuring fifty feet long manned by twenty-five Malay paddlers sitting crossed-legged on a slated deck, a portion towards the stern was reserved for the Tuan where a mattress was arranged under a Kajang awning. 45 miles to Simanggang where the journey can be dangerous. The most dangerous being the tidal bore which can travel at 10 to 12 miles per hour. Finally sweeping around a bend, a long reach brings into sight a green hill standing cliff-like from the water, crowned with a black and white fort called Fort Alice, the home of regional government and law for the second division. The original Batang Lupar fort was built in 1849 to command the entrance to the Skrang River, it was later moved to the hill at Simanggang and named Fort Alice after Rajah Charles Brooke's sister. The fort was built of massive Belian or ironwood in an oblong enclosing a courtyard. The front-facing the water was the great courtroom, containing an inadequate table with green baize from which justice was administered. Some wooden safes, also some small tables for the junior officers and Chinese clerks. Down the center forming a nave were racks of Snider carbines for the garrison rangers or Malay levies. On brackets behind the seat of justice were some earthenware heads, which a former resident hoped the Dyaks might collect instead of human trophies. From the courtroom, a door led to the officer's quarters a living room, and two bedrooms. The assistant Resident had his room at the other end of the Fort in close conjunction with the Ranger's sleeping quarters.

Residents Bungalow , The Jail & farm with Cattle in the foreground, Simanggang

Behind the Fort was the Jail with the other quarters for

police and military. Beyond stretched some farmland acres which were tended by

the prisoners. The short-horned cattle were imported by the Rajah and were milked

and occasionally slaughtered to provide meat and milk for the government officials.

Sheep were also reared along with chicken.

The Chinese Bazaar was a row of wooden opened-fronted

shops extending along the riverbank. The Malay population of Simanggang lived

in two separate villages, the Kampung Ulu above the fort and the Kampong Hilir

below. The Kampung Uu considered itself more aristocratic because it was home to

the senior native officer Tuanku Putra who was the son of the prime pirate who

had been defeated by James Brooke at Pemutus in 1844. These Malays were

gradually given important positions in the government. They became the most

reliable and loyal supporters of the Rajah's rule.

18th March 1908 Appointment of British Agent for Sarawak

FAW

Page-Turner 5th August 1908 – 9th April 1909 granted and

took Leave. He arrived in Brighton 3rd Sept 1908, returning to

Sarawak 12th March 1909

Frances

Helen Page-Turner (sister) visited in October 1910

Sylvia seated center , on board a Steam Yacht

21st March 1909 Pangeran Omar affair closed, Ulu

Strap

FAW Page-Turner 1st May 1910 – 15th June 1910 Actg i/c Batang Lupar Vice A.B.Ward

FAW

Page-Turner 16h June 1910 – 30th June 1914 Duty 3rd Division

During the great war of 1914-1918 all the European officers working in Sarawak were given special dispensation, however, some junior officers returned to their mother country to fight for their country. News from home was very sporadic. There were some initial disruptions in terms of food prices escalating however the government stepped in to control prices. There was a drainage of men from rubber plantations and other food growers. There was alarm when Turkey entered the war pitting a Muslim country against the allies. This worry did not amount to much of a worry.

20th November 1912 Constitution of Sarawak State

Advisory Council in England

In 1912 the senior administrative service of Sarawak consisted of 4 residents 16 junior officers governing some 300-400,000 people.

FAW Page-Turner and Dalmation and Frances Page-Turner

FAW Page-Turner July 1914 – 11th March 1915 Leave , arriving in the Uk 6th Sept 1914, leaving the Uk for Sarawak 6th Feb 1915 from Tilbury in the P&O SS Malwa for Kuching via Singapore

5th October 1914 Ex-Penghulu Ngumbang died

22nd February 1915 1st Gat Expedition

14th May 1915 Mujong Expedition

Photographs by Dr Charles

Hose and Robert Shelford. Many of these photographs were reproduced in Hose's

own books and those of other writers. F.A.W Page-Turner appears in quite a number

of these photos and must have organised the expedition in his capacity as Resident of the district where the expedition was carried out and where these

photographs were taken. Dr Hose was a keen amateur photographer and also made a

large collection of fauna and flora from Sarawak. He died on November 14th 1929

and, subsequently, a large part of his collection of Sarawak material was

presented to the British Museum. These photos refer to an expedition that will

have been taken anytime between 1907 and 1920 when Dr Charles Hose visited Sarawak

following his retirement in 1907.

Charles Hose was born in

Willan, Hertfordshire on October 12th 1863. He was the son of Thomas Charles

Hose and Fanny (née Goodfellow). He was educated at Felsted and Jesus College,

Cambridge. He married Emily Ravn in 1905 and had one son and one daughter.

Hose entered the service of

the Raja of Sarawak as a Sarawak cadet in March 1884. In 1888 he was

Officer-in-Charge of the Baram District. In January 1891 he was Resident, 2nd

class. By May 1904 he was Resident, 3rd Division, a member of Supreme Council and

Judge of the Supreme Court of Sarawak. He retired in 1907 but he revisited

Sarawak in 1909 and 1920. From 1916 to 1919 he was Superintendent of H.M.

Explosives Factory, Kings Lynn. In 1919 he was a member of the Sarawak State

Advisory Council at Westminster. In 1924 at the British Empire Exhibition in

Wembley he was the Director of Agricultural and Industrial Exhibits, Sarawak

Pavilion.

The Sarawak Civil Service List gives further details of his activities in Sarawak: 'While in Sarawak [Hose] distinguished himself as a geographer, anthropologist and collector of natural history specimens. His numerous journeys in the Baram District, which he was the first Officer to explore thoroughly, brought him into contact with many interior tribes, who, through his influence, came under Sarawak control and made peace with Sarawak tribes.

Conducted a successful expedition in the

Ulu Rejang with a force of two hundred Kayans against Dyaks on Bukit Batu April

to June 1904. While Resident of the Third Division was instrumental in

effecting the surrender of Bantin and disaffected tribes of the Empran, Engkari

and Kanowit districts. After leaving Sarawak he was responsible for bringing to

the notice of the Anglo-Saxon Petroleum Company the possibilities of the Miri

Oilfield and for conducting negotiations between H.H. the Rajah and that

Company, resulting in the exploitation of that field, which, in point of production

of oil, is now the second largest within the countries under the control of

protection of Great Britain'.

Expedition Canoes at rest stop, F.A.W. Page-Turner the Resident and leader

standing wearing a straw hat with his back to the camera

Robert Walter Campbell Shelford was born in Singapore on the 3rd August 1872. He was educated at King's College, London and Emmanuel College, Cambridge. From 1895 to 1897 he was a demonstrator in biology at the Yorkshire College, Leeds. From 1897 to 1904 he was the curator of the Sarawak Museum, Kuching. Shelford was in the Hope Department, Oxford University Museum 1905-12. Shelford married the daughter of Reverend Alfred Richardson in June 1908 and died at Margate on the 22nd June 1912.

FAW

Page-Turner 16th March 1916

Duty Mukah

FAW Page-Turner 1st November 1915 – 31st December 1916 Acting Resident 2nd Division Simanggang

FAW Page-Turner 1st Jan 1917 - 1st October 1930 confirmed as Resident 2nd Division Simanggang

17th May 1917 Death of Sir Charles Brooke

24th May 1917 Proclamation of Rajah Vyner Brooke

22nd July 1918 Installation of Rajah Brooke

(crimson banner spanned the road at the stone landing place, supported by two tall masts covered by heraldic shields and little miniature flags (long triumphal archway of these masts, hanging with garlands of coloured paper roses and reaching as far as the doorway of the courthouse. Sarawak Rangers and police took up positions along the route. At 9 am the Rajah Mudah and party left the Astana bearing the sword of state upon a yellow cushion and taken across the river by the state barge (originally gifted by the King of Siam).

The party was received at the landing place by the members of the

supreme council. The Rajah walks ahead sheltered by the official Royal

Umbrella. Members of the supreme council

fell in line behind the Royal Party. The

Party processed to the Court House. Rajah wearing his green and gold uniform.

Tuan Mudah in Khaki.

Crossing the platform were assembled Members of the council of Negri, the Sarawak Government Officers and their wives, and all the European guests.

The Law Courts Kuching from the Astana, Kuching

FAW Page-Turner 2nd July 1918 appointed Member of the Council of Negri

The first legislative assembly in Sarawak was formed during the rule of the White Rajahs. The General Council (Majlis Umum) of the Kingdom of Sarawak was convened on 8 September 1867 by Charles Brooke, the Rajah Muda under the orders of James Brooke, then the Rajah of Sarawak. Its members were chosen from local tribe leaders who were thought to be capable of assisting Brooke in administering the kingdom. The General Council later evolved into the Council Negri in 1865. It consisted of Chieftains of the tribes, together with the chief European and Malay officials of Kuching and the European Residents. They were to meet at least every three years, to endorse any major political decision or constitutional development and to discuss plans for the future. The Council Negri first met in Bintulu.

In 1976, Council Negri formally changed its name to Dewan Undangan Negeri (legislative assembly) through an amendment to the Sarawak constitution. The Assembly is also the oldest legislature in Malaysia and one of the oldest continuously functioning legislatures in the world, being established on 8 September 1867 as the General Council under the Raj of Sarawak.

There was never any cause for discussion, and the meeting

became more or less a formality to enable the Rajah to greet all his principal

officers, and at the same time, to give the outstation chiefs a week's holiday

in Kuching at government expense.

The Council of Negri met in the large dining room at the Astana the table extending the whole length of the room was surrounded by solemn-faced natives, for the most part, resplendent in flowing robes and twisted turbans of varied hues. Malays, Dyaks, Muruts, and Kayans, all races of Sarawak were represented there.

An armchair at the head awaited the Rajah. The

Europeans were grouped in a semi-circle behind. The Europeans were dressed in

navy blue suits with “hard-boiled” shirts. After all, the Sarawak motto “ Dum

spiro Spero” was always interpreted to mean “ While I perspire I Hope”. A Low buzz of conversation filled the room: and

then a “stomp stomp” was heard along the veranda. There was a rustle as the

assembly rose from their seats but in dead silence, the Rajah strode into the

Room. He alone wore the gorgeous Sarawak Uniform, and he was unaccompanied. To

the childlike natives, he was everything, their father, their King almost their

God. Bowing to the assembly the Rajah took his seat and the initiation of the

new members proceeded at once. Natives were called first and standing before

their ruler were sworn in. Mohammedans took their oath on the Koran to be

faithful to the Rajah. Kayans swore by the tooth of the tiger; Europeans had

the chaplain with a Bible to register their fidelity. As the candidates came

forward one by one, the Rajah made eye contact with each candidate who recited

their oath to the Rajah. The Rajah then

made a speech. A banquet followed where the table was displayed with all the

state finery with the Rajah at the head surrounded by his officers. Each

resident looked after his group of native officers it entailed instructing them

in the art of eating with a knife and a fork and making sure they did not overindulge

in the fine wines or offend the laws of decency.

5th April 1919 2nd Gat Expedition

FAW

Page-Turner 20th April 1920 -

8th Jan 1921 Leave

F A W Page-Turner with Delia and others on leave

FAW

Page-Turner 1st July 1920 Officer Class II

4th August 1920 Dayak Peace-making at Simanggang

There were two peace-making ceremonies held between the 1907-1924 period at Kapit. On December 4. 1907 H.S.B Johnson reported:

In fact, between 1907 to 1916, the Iban from Balleh, Katibas, Machan, Naman, and Julau seemingly coordinated their raids against the Punan who had reoccupied the Pila, Merit, and Metah following the peace deal. Determined to get rid of the Punan from these areas, the Iban launched the biggest raid, after 1896. It was a party of 400 strong consisting of Gaat Iban.

Mr Gifford was on his way returning to Kapit from Belaga when he learned of the Gaat’s planned raid. He quickly alerted the Punan of the impending raid and relayed a message down to Mr Lang at Sibu for immediate reinforcement of about 50 well-armed Malay rangers. Gifford then led 200 strong Government forces, made up of Malays and Kayans back upriver, and encountered the 400-strong Iban war party at Pila.

The latter made a feint to attack the Government force but were shot down to the number of about 200. The Iban party lost all their fifteen boats and drowned trying to escape capture. Mr Gifford’s force suffered no casualty, except for a wounded Fortman. He highly commended Abang Aboi, a Native Chief at Kapit, the Rangers, Malays for showing conspicuous bravery. However, rebuked the 80 Kayan, whom Gifford said were “useless” (SG May 1, 1916:78).

After the 1916 bloodied Gaat's Iban raid, the Government restricted Punan movement from Bikei rapid (Iban’s Mikai rapid) downriver. They were no longer allowed to reclaim and reoccupy their ancestral lands in the Pila and Merit region. In 1919, a group of Iban tried to settle at Sama River, above Pelagus. The group quickly reprimanded them and told them to return downriver near Kapit.

However, succumbing to Iban’s pressure, the Government relented. But to avoid racial flare-ups, they arranged for another peace-making ceremony in 1924. This time, it was much grander, involving not only the Kajang (Punan, Sekapan, and Kajaman), Kayan, and Kenyah of Sarawak, but also those from Kalimantan.

Shortly thereafter, the Government began to allow, mostly law-abiding, Roman Catholic Katibas Iban to move into the Pila area (Pringle 1970). A Christian mission was duly set up in the area. After opening the floodgate, droves of other Iban from downriver started moving into the upper Pelagus. By 1935, their longhouses had spread, a mere four kilometres from Punan Ba village.

On arriving at Simanggang the Rajah and his party were met by two government Officers stationed there. An immense crowd of local people were lined up on both sides of the path, many of whom the Rajah knew both by sight and name since he had recently relinquished his role as Resident of the 2nd Division. All the Pengulus (Chiefs) were dressed alike in a bright uniform consisting of a black coat, red trousers, and a yellow sash, the colours of Sarawak. Round their heads were wound small turbans of the same colours. the Rajah spoke a little word to each one in turn and then passed on into the bungalow. There he interviewed the chiefs and Chinese Towkays, settling cases that could only be settled by his final word.

The following day thousands of Dyaks arrived and stationed themselves upon an open space allotted to them. On a stand covered by crimson bunting sat all the native officials and important people of the station. The rival chiefs are in two separate groups. In the center were 60 jars about 3.5 ft high and 18 inches in diameter. They were split into 2 groups and were guarded by the Sarawak Rangers. The Jars were provided by the up-river and down-river tribes in equal numbers so that they could be exchanged between them and kept in the houses of the headmen as tokens of the settlement of their feuds.

The Rajah called the rival chiefs to approach him, addressing them in Dyak asking them to realize the solemnity of the occasion, and telling them the peace-making had been arranged to wipe out the old scores. He further charged them to do away with the practice of head-hunting forever.

The two rival chiefs stepped forward and two small pigs were placed in the centre of the arena, the chiefs standing by them with spears ready in their hands. They carried shields covered with curious designs and decorated with the same gruesome trophies of human hair. The pigs were then stabbed with the spears and thrown into the river.The Jars and brass gongs, brass tobacco boxes spears, and blankets were distributed among the chiefs.

Both before and following James Brooke's installation as the ruler of Sarawak in 1841, at the instigation and with the support of the Sarawak Malays, conflict among the indigenous communities in northwest Borneo was at epidemic levels.

Drawing on indigenous traditions of conflict resolution, all three Rajahs pursued peace-making ceremonies which sought to reconcile traditional enemies with each other, and with the Sarawak Government. These ceremonies did not attempt to untangle the grievances which had been created by generations of complex conflict but sought to make peace by helping communities to draw a line through past offences, looking instead towards a peaceful and prosperous future together under the authority of the Government.

The 1924 Peace-making ceremony at Kapit was a culmination of efforts by so many stakeholders, including the Sarawak Government, to establish such a future. The enduring and powerful identity that is shared by Sarawak people today, characterized by the late Tok Nan, as "anak Sarawak", is a testament to their success.

This anniversary of the Kapit Peace-making of 1924 speaks to the hopes of so many of our ancestors to live in peace and friendship with each other.

The Regatta at the Marudi peace-making in 1899 was carefully

organized to maximize the participation of local chiefs in the management of

the event. • They were made into judges, stewards, and umpires alongside the

Brooke officers. • The idea was to provide an alternative to headhunting for

energetic ambitious men aspiring for fame. This regatta was the climax of other

peacemakings held in Baram district over the previous years in 1895 onwards.

Peacemaking was a period that laid the foundations for the Brooke state and

eventually, the Sarawak State as we know it today. • Peace-making was a process

–that was documented by the officers of the Brooke state early 1840s to the

1924 Kapit Peace-making and Long Jawe in 1967. • Peacemaking generated the

legacy of sociality that people experience in Sarawak –the easy partaking of

regattas, festivals and food between peoples of different traditions and

religions. • Peace-making was based on local customary law adat which has

become codified as the basis for dispute resolution at the local level.

Spotlight on Sarawak: The Baram Regatta – The Legacy of the Regatta:

Peace-making in the Baram, Dr Valerie Mashman

The Week was just one long social whirl because, besides the races, there were sports competitions of all sorts, and lavish parties every night, so that by the end of the week practically everyone was exhausted.

Fancy Dress Kuching, Sylvia Brooke seated Center , F A W Page-Turner to her left

The Ranees daughter seated by her on the ground

Iban Women from the 2nd Division visit the Race Day with other tribes from Sarawak

To start with, Sarawak contended itself with native ponies imported from North Borneo ranging from 12 to 13 hands. As the years passed ideas expanded and soon the horsey men were subscribing for griffins limited to fourteen hands imported from Australia. The two-day race meetings were public holidays. There was a grandstand for the Europeans and principal Sarwakians, a team room for the ladies, and a bar for the men. Opposite the grandstand, a long line of native huts built on high posts extended along the rails. They were for the Malay ladies who sat there in all their finery. The Europeans who lived in Sarawak were expected to help with the races, helping with starting the races, and stewards in the paddock and grandstands.

Charles Vyner Brooke the 3rd Rajah and his officers

FAW Page-Turner 1st from left at the Astana

Most of the Officers stayed at the Astana. Formal dinners

were held with processions to the dining table. The Astana was the palace that was

built for the second Rajah after the first Rajah’s bungalow was burnt down by

the Chinese insurrection. The building

is eclectic in style, with a Gothic tower forming the entrance, and on either

side great wings with high-pitched roofs of wooden shingles, with reception

rooms and bedrooms all on the first floor, supported on whitewashed brick

arcades, with the kitchens and bathrooms on the ground floor. Tea parties were

held on Tuesdays for the whole European community. Now and then there were

dinner parties followed by music. The Rajah often entertained. Punctuality was

a mania with Charles Brooke, he dined at eight, and as the time gun boomed

forth, he led the way to the dining room and woe betide anyone late. A feature

of the Astana dinners was the presence of the Sarawak Rangers in uniform,

stationed at intervals around the room bearing large palm-leaf fans of the type

seen in the picture of Cleopatra; these were waved to and from to cool the air

as a substitute for the more usual creaking punkahs. After dinner, if the ladies

were present, there was perhaps a little music, but at ten o’clock punctually

the Rajah rose, shook hands, went off to bed, and left his guests to depart. If

it was a man’s party, the Rajah took his seat on a side veranda with the rest

of the company in a line opposite him, all uncomfortably seated on iron

benches.

The whole system of government in Sarawak was a personal

and patriarchal rule. The welfare of the people was of utter importance to the

Rajahs in particular Charles Brooke. The personal rule is what the Asiatic

respects and understands. He wants government from a man who is human like

himself and can understand his frailties.

Rajah C V Brooke & his daughters with F A W Page-Turner far right

Rajah C V Brooke with FAW Page-Turner on his right & other

Government Officers & wives at the Astana

Government Officers on the Verandah circa 1920's

The social element in Kuching was mainly represented by

the government class, however, the Borneo Company did a lot of entertaining too,

and one or two of the catholic and Anglican missionaries. Dinner parties

constituted the most common form of social gatherings. Bridge, of course, was

not known and poker generally finished up the evenings.

FAW

Page-Turner 1st September 1922 appointed Officer Class 1 and

Resident of the 2nd Division,

The Resident F A W Page-Turner & his staff

Fort Alice Simanggang 1929

FAW Page-Turner was the first European officer to hold this title since 1875, he remained with this appointment until he retired in 1930. According to his obituary, Mr F A W Page-Turner had wide experience and understanding with the Dyaks and enjoyed their entire confidence. His administration of the second division was a complete success and his name was still one to conjure with among the older natives. “Tuan S’tarna” as he was always known.

Detail : FAW Page-Turner seated on the Bow

accompanied by a Junior Officer

He was known to be a just man and a wise and sympathetic administrator. Mr Page-Turner served on numerous expeditions against head-hunters and other malefactors, and it was during one of these that an incident occurred which provides a good illustration of his personal courage.

F A W Page-Turner seated center with Colleagues to right & left

with Iban Women and children

After halting for the night Mr Page-Turner went down to bathe at a small stream, and believing the enemy to be far away, he dispensed with all the usual guards. Suddenly the foliage on the opposite bank parted to reveal a group of hostile Dyaks, all fully armed and definitely ready for mischief. No whit disconcerted Mr Page-Turner who it should be remembered, was quite helpless, did not lose his head but started to rate them soundly for their lack of courtesy, asking them how they dared to disturb a European in the course of his ablutions! No Dyaks likes to be thought of as lacking in manners, and it is related that this particular party grew abashed at Tuan’s well-chosen words and eventually retired from the scene in surly embarrassment, their departure it is said being accelerated by a few final stinging remarks and a shower of pebbles from the irate bather!

F A W Page-Turner standing far left with Iban Women & Children on the Long House Ruai

The one characteristic of the Dyak that caused the most concern for the Sarawak government and the Resident was the custom of headhunting. The Dyak race consisted of numerous clans analogous to the clans of the Scottish highlands. Quarrels often arose and people got killed, thus feuds were started and retaliation for injuries became a law. From these beginnings headhunting became a sort of instinct, an obligation, and a religion. For example, it was difficult for a young man to marry unless he could present intended with a human trophy.

Head Hunters Trophies in Long House

When a relative

died an enemy’s head was necessary to allay the mourning and to provide the

deceased with an attendant in the world beyond. The worst aspect of this custom

was that it didn’t matter whether the head was of a woman or child let alone a

man of any age. Dyak’s were only just brought into the ways of the European

civilization less than 100 years ago. It was the responsibility of the Resident

and his staff along with the Christian missionaries to eradicate this barbaric

custom.

FAW Page-Turner 26th September 1925 Long service Decoration

FAW

Page-Turner 1st July 1927 -28th January 1928 Leave

FAW

Page-Turner 1st October 1930

Retired on Pension

In F.A.W Page-Turner's obituary is written the following observation; “Those who remember Simanggang in Mr Page-Turner's time will agree that with his retirement an epoch came to an end. He loved Simanggang and the whole station reflected his personality. It was a station steeped in tradition and the various “adats” that remained in force gave a particular charm. When Mr Page-Turner left Simanggang he took with him the last surviving traces of an old order which made up in dignity for anything that it might have lacked in modern efficiency and hustle. In 1930 Mr Page-Turner inherited a considerable estate in Ambrosden England from his late brother, he married in the following year.”

Although the much-traveled Somerset Maugham is famous for his short

stories with a Malayan setting, he did not spend all that much time in the

country. He first visited what was then the British Colony of the Federated

Malay States in 1921. His stay lasted for six months, three of them passed in a

sanatorium in Java due to illness. His second and last visit came in 1925 when

he was there for four months. This was enough, however, to collect the material

he sought.

On Saturday 2 April 1921, after an eventful voyage from Singapore, a wizened middle-aged Englishman walked down the gangplank of the steamship Kuching and onto the soil of Sarawak. He was William Somerset Maugham, a renowned playwright, novelist, and short story writer, on an expedition to the East in search of raw material for future literary creations. He was accompanied by his secretary Gerald Haxton, but not by his typewriter, which had been lost in transit, along with the keys to his luggage. It was not an auspicious start to his visit. Although opening the luggage was facilitated by the lock-picking skills of a convicted murderer whom the authorities put at Maugham’s disposal, things would only get worse for the writer and his companion. Maugham did not have the opportunity to pay his respects to Rajah Vyner Brooke, who was in England at the time, but was received hospitably by Brooke’s Aide-de-Camp, Captain Barry Gifford. A trip to the interior was quickly arranged for him, through the good offices of the District Officer of Simanggang (now Sri Aman).

That officer’s surname would

surely have brought a smile to the face of a best-selling writer: it was F A W Page-Turner.

A motor launch conveyed Maugham, Haxton, and Gifford from Kuching to Simanggang

on the Batang Lupar. A canoe then took them along the Skrang River to an Iban

longhouse, where they spent two days. Maugham soaked up local colour and, as

was his custom, filled page upon page of his notebook with impressions of the

flora, fauna, landscape, and people, for possible use in his future writings.

The party then set off downstream

in a canoe crewed by eight trusted convicts, intending to rendezvous with the

launch and return to Kuching. The Batang Lupar was (and still is) well known

for its tidal bore, a wave moving rapidly upstream caused by a high tide from a

wide river mouth squeezing into a narrowing river. Unfortunately, as District

Officer F A W Page-Turner later angrily reported, the local police constable

failed to warn the visitors about when the bore was expected. He should have

advised them to shelter at Stumbin. As luck would have it, they met the bore at

Lubok Naga – ‘about the worst place in the river when the bore is at its

height’, as the Sarawak Gazette later reported. An eight-foot ‘wall of rushing

water’ engulfed their craft, threw them all into the river, and carried them

rapidly upstream as they alternately grabbed gunwale and keel as the boat

tumbled in the torrent. ‘We all scrambled round it like squirrels in a cage,’

Maugham recalled. His first impulse was to try to swim to safety but the others

shouted to him to hang on to the boat. After twenty or thirty minutes – Maugham

lost track of time – one of the prisoners passed him a makeshift lifebelt: one

of the mattresses on which the passengers had been lying in the canoe. They all

struggled towards the river bank, waded through knee-deep black mud, and lay

down on the ground, exhausted. A passing canoe took them to a nearby longhouse,

where, clad in a dry sarong and fortified with ‘plenty of drink’, Maugham later

gazed at the new moon ‘thankful to be alive’. ‘I couldn’t help thinking that I

might at that moment have been a corpse floating along with everyone else.

The next day, ‘cut about, bruised from head to

foot’, Maugham and Haxton reboarded the launch at Bijat to return to Kuching.

On Tuesday 19 April they rejoined the S.S. Kuching, bound for Singapore, where

they purchased replacements for the belongings now lying on the riverbed. They

then visited Brunei and British North Borneo (now Sabah), but never again did

they grace Sarawak’s shores. The near-death experience at the hands of the

tidal bore was not forgotten, however, and is immortalized in one of Maugham’s

‘Malay’ tales. In his writings, Maugham made free use of characters whom he

encountered and events that he experienced himself or about which he heard

during his travels. Names were changed of course, occurrences were transposed,

embroidered, conflated, and adapted. ‘I have never claimed to create anything

out of nothing,’ Maugham declared. ‘I have always needed an incident or a

character as a starting point, but I have exercised imagination, invention, and

a sense of the dramatic to make it something of my own.’ But people could often

recognize themselves in his stories: those set in the East often depicted the

antics of expatriates. Those who saw themselves exposed in a short story

pretended to be angry.

Conversely, as W. J. Chater writes in Sarawak

long ago, many people not depicted were jealous that they had been overlooked

by the master storyteller. In the short story The Yellow Streak, first

published in magazines in 1925 and later in collections of his short stories,

Maugham drew upon his Batang Lupar experience. In this story Sarawak is thinly

disguised as ‘Sembulu’, the Rajah becomes a Sultan, and Kuching is dubbed

‘Kuala Solor’. A colonial officer named Izzart is escorting a mining engineer

named Campion downriver to meet a steamer which is to take them to the capital.

Campion has heard of the river’s tidal bore. ‘Oh, that’s all right. We needn’t

worry about that,’ replies Izzart nonchalantly. When they encounter the bore,

however, they are terrified. ‘It might have been ten or twelve feet high, but

you could measure it only with your horror.’ I shall not reveal the denouement,

in case you have not yet read this story. With its twists and turns The Yellow

Streak is still worth reading for its depiction of inter-racial relations,

snobbery, and the frailty of human nature, set against an evocative and for an

Anglophone reader exotic backdrop. Maugham conjures up an image of a mysterious

Orient and portrays the foibles and failings of many expatriates amongst an

array of stereotypes of indigenous peoples. As Chater noted, Maugham did not

make himself universally popular. One expatriate expressed a ‘strong objection

to the deliberate manner in which Mr. Maugham has set out in all his stories to

disparage this country, to belittle the natives, to blacken the characters of

the Europeans.’ It is perhaps not surprising that, a few years later, when

Maugham informed the Rajah that he would like to revisit Sarawak, ‘he received

a polite reply informing him that it would not be convenient.’ One visit was

enough, however, for Maugham to capture most vividly the half-hour desperate

struggle of a vulnerable group of travellers against a monster wave. Today we

can only faintly grasp the full horror of this experience when we watch the

progress of the bore from the safety of the observation tower on the river bank

at Sri Aman.

During his travels through remote jungle places, he would put up for the

night at the homes of colonial officials who had not seen a compatriot for

months on end and who accordingly were bursting with chat and tales to tell. One

of these was with F A W Page-Turner who was a resident of Simanggang 1915-1930.

Where Maugham was able to observe much of his material for two of his classic

short stories “The Outstation” and “The

Yellow Streak”. The character of “Wharburton”

who was the Resident in “The Outstation” might well be based on Somerset Maugham’s

detailed character observations of the senior officers based in Simanggang. F A W Page-Turner who was the Resident of the

2nd Division almost certainly hosted Somerset Maughan at the Residents quarters in

Simanggang or at one of Page-Turner's junior officers residencies. Unlike certain other Malayan stories,

"The Outstation" cannot be traced directly to a real person or place,

although it probably had its germ in something told to Maugham over a

hospitable gin pahit. It vividly illustrates his primary

interest, which was to study the reactions of his compatriots when placed in an

exotic context. "The Outstation" first appeared in the

collection The Casuarina Tree (1926).

The story concerns Mr. Warburton, the resident of a distant outstation

in Borneo who always dresses for dinner at a set time every night, chooses his

courses from a menu in French, and is waited on by Malay servants immaculately

turned out. He peruses The Times, especially the social news

of lords and ladies, even though it arrives six weeks late. He has disciplined

himself to read each issue in strict sequence, however much he is longing to

know the course of certain events. When he is on duty, his attire is invariably

perfect, for he believes that if a man succumbs to the influences around him

and loses his self-respect he will also lose the respect of the natives. Yet

over the years he has evolved into a skilful administrator and has acquired a

profound knowledge of, and affection for, the Malays, their customs, and their

language, although he remains an English gentleman who will never "go

native."

An assistant is sent out to help him with the extra work that has

developed. The assistant, a shabby, blunt-spoken man named Cooper, is

everything Warburton is not, and he is at first amused by the stately dinner

routine and chuckles at the resident's pomposity. Cooper has been neither

to public school nor to a university, and during the war he served in the ranks.

"I wonder why on earth they've sent me a fellow like that?" Warburton

thinks to himself, especially when he learns that his assistant, a colonial

with an inferiority complex, bullies the Malays and treats them harshly. In

return, Cooper earns their dislike. Small irritations become large ones between

the two men. The impious Cooper tears open Warburton's sacrosanct copies

of The Times and dares to read them first and leave them in an

untidy condition. Then Warburton is obliged, for perfectly valid reasons, to

countermand one of Cooper's orders to his men. Their mutual antagonism erupts

into a violent confrontation when Cooper accuses him openly of being a snob and

humiliates him by reporting that he is a standing joke among his colleagues up

and down the country. But Warburton has the last laugh. Cooper sacks his Malay

servant, having held back his wages, treated him with injustice, and insulted

him. Warburton, from his deep acquaintance with the passionate and vengeful

mind of the Malays, warns him that he is running a grave risk. Cooper disdains

him, but a few days later he is found in his bed, a dagger through his heart.

Warburton settles down again happily to his ceremonious dinners for one, in

full evening dress, and to his thrilled absorption in the social columns

of The Times.

It is one of Maugham's great strengths that he does not take sides but

rather lays out the facts with apparent objectiveness in order to round out his

characters. Warburton is an outrageous snob, but he is also a just

administrator who is respected by the Malays, whom he instinctively understands

and among whom he wishes to be buried when he dies. Cooper is a racist cad,

tactless and uncouth, but within his limits, he is conscientious and

hardworking, grimly determined to get the most out of those whom he is employed

to supervise. Local colour is deftly touched in to highlight the encounter

between two types of men who, because of their different social classes, would

never have met in England, whereas in Malaya their close juxtaposition

emphasizes the unbridgeable gulf that separates them. Maugham's eye for

dramatic effect lends the narrative a power that propels the story to its

inevitable end. "The Outstation," which the contemporary critic Edwin

Muir declared to be "one of the best stories written in our time,"

remains a prime example of Maugham's gift for taut structure.

“The Outstation” by Somerset Maughan 1926

The

new assistant arrived in the afternoon. When the Resident, Mr. Warburton, was

told that the prahu was in sight he put on his solar topee and went down to the

landing stage. The guard, eight little Dyak soldiers, stood to attention as he

passed. He noted with satisfaction that their bearing was martial, their

uniforms neat and clean, and their guns shining. They were a credit to him.

From the landing stage, he watched the bend of the river around which in a

moment the boat would sweep. He looked very smart in his spotless ducks and

white shoes. He held under his arm a gold-headed Malacca cane which had been

given him by the Sultan of Perak. He awaited the newcomer with mingled

feelings. There was more work in the district than one man could properly do,

and during his periodical tours of the country under his charge it had been

inconvenient to leave the station in the hands of a native clerk, but he had

been so long the only white man there that he could not face the arrival of

another without misgiving. He was accustomed to loneliness. During the war he

had not seen an English face for three years; and once when he was instructed

to put up an afforestation officer he was seized with panic, so that when the

stranger was due to arrive, having arranged everything for his reception, he

wrote a note telling him he was obliged to go up-river, and fled; he remained

away till he was informed by a messenger that his guest had left.

Now

the prahu appeared in the broad reach. It was manned by prisoners, Dyaks under

various sentences, and a couple of warders were waiting on the landing stage to

take them back to jail. They were sturdy fellows, used to the river, and they

rowed with a powerful stroke. As the boat reached the side a man got out from

under the Attap awning and stepped on shore. The guard presented arms.

"Here

we are at last. By God, I`m as cramped as the devil. I`ve brought you your

mail."

He

spoke with exuberant joviality. Mr. Warburton politely held out his hand.

"Mr.

Cooper, I presume?"

"That`s

right. Were you expecting anyone else?"

The

question had a facetious intent, but the Resident did not smile.

"My

name is Warburton. I`ll show you your quarters. They`ll bring your kit

along."

He