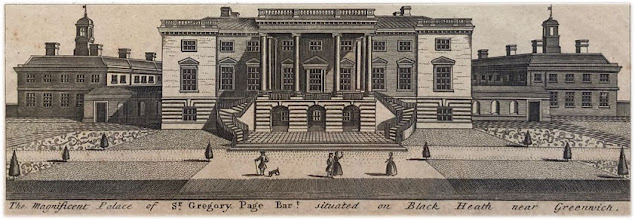

Wricklemarsh seat of Sir Gregory Page 2nd Bt (c.1695 – 1775)

Wricklemarsh seat of Sir Gregory Page 2nd Bt

(c.1695 – 1775)

Sir Gregory Page. the second baronet, was 30 when he succeeded his father and in the following year, he married Martha, daughter of Robert Kenward of Yalding, Kent. This Sir Gregory appears not to have concerned himself greatly with the family business. Indeed he had probably little need to do so for with his father’s accumulated fortune, substantially ’ augmented by the successful South Sea speculation, he was described as “ the richest commoner in England ”. He greatly extended his father‘s small Greenwich property by investment in real estate with the following purchases which made him one of the most important land-owners in south-east England. Thus, when Sir Gregory Page 2nd Bt, came into his rights as head of the family only two or three members lived at Greenwich. With neither a family to worry about nor a living to be earned, Gregory Page set about devoting the middle years of his life to the purchase of land. This may have been because of the distant memory of sequestration laws that arose from the Commonwealth, or the thought that the reprisals against South Sea company A profiteers may be extended to non-directional shareholders, we cannot now know. But then, as now, the land was the safest bank into which money could be and, in the event of taxation, it would be easier to undervalue the land than gold, silver, and other commodities.

List of land purchases

1717 Land at Crayford from Messrs. Middleton and Winder £3,500.

1722 Land at East Greenwich from Mr. Bennett £750.

1723 The Wricklemarsh estate from the trustees of Sir John Morden £9,000.

1724 Land in Mark Lane and Seething Lane, London, £15,000.

1724 The Westcombe estate from the heirs of Sir Michael Biddulph £12,000.

1724 Milton Bryant, Bedfordshire, from Lord Bathurst £12,350.

Battlesden, Bedfordshire, from Lady Bathurst £40,408. For his brother Thomas

Page

1726 Land at Kidbrooke from Mr. Heppenstall £350.

1727 Land at Lewisham from Lord Dartmouth £500.

1738 The estates of Well Hall and East Home from Sir Edward Deering, Sir

Rowland Wynn, and Mr.William Strickland whose wives were descendants of the Ropers

£19,000. Page demolished the Tudor

house at Well Hall and built the one which survived until about 1930.

1733/4 Land at Lee, Eltham and Kidbrooke from Mr.Lewin £3,400.

1742/3 Land at Lee from Mr.Papillion £300.

Wricklemarsh was owned by Sir John Morden who left his principal estate to Modern College which he founded. The estate was previously called Witenemers in the Doomsday Book held at that time by the son of Turald, of Rochester. The manor house together with four tenements was sold for 1,950 in 1669 to Sir John Morden, who in his will devised ' his mansion-house, called Wricklemarsh, with all the orchards, gardens, walks, ponds, and appurtenances, and as many acres of land, next adjoining to the said house, as amounted to the yearly value of 100 at the least,' to his wife for life. Upon the death of Lady Morden, the estate was sold under a decree in Chancery to Sir Gregory Page, who pulled down the old house and erected in its place a magnificent mansion, which was then one of the finest seats in England belonging to a private gentleman.

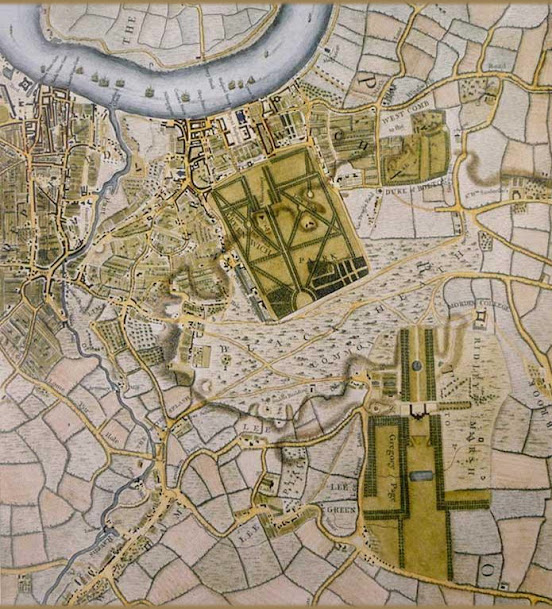

The Trustees tried hard to find a buyer of the Wricklemarsh estate. There is no record of any enthusiastic would-be purchasers and it was not until 1723 that a worthwhile offer was received from Sir Gregory Page, 2nd Baronet, a man of prodigious wealth who lived on the northeast corner of Greenwich Park. Page gave £9000 for the property: it included the old house, set in a 22-acre park. and a little over 271 acres of agricultural land stretching South from Blackheath towards the Lee to Eltham roads. Some of the fields were let to Richardson Headly, Henry Foster, William Richardson, and Edward Saunders. Edward Sadler and Henry Ellison were all farmers or smallholders. The deal was a total freehold purchase and Page agreed to obtain the private act of Parliament necessary to register his absolute title to the land The Act was passed in May 1723 and the transfer took effect in August of the same year. Morden College was now financially secure, set in its own free ground of Great Stone Field on the northeast corner of the Wricklemarsh estate. Page was set to make great changes to his new estate and sweep away much of the old farmstead and smallholding appearance of Morden’s time. He turned Wricklemarsh into a grand park, the fitting home for one of the richest men in England.

The purchase was confirmed in August 1723: it included Morden's old house, all the parkland and agricultural land attached 7 about 280 acres in all 7 as well as small parcels of land around about, including Ancock's Hill (Grotes Place], and a house known as the Three Tuns, This last may have been the public house in the middle of the Village but, if so. this is curious because the central triangle of the Village was a wasteland in the Manor of Lewisham part of the Dartmouth freehold. it may be that there was a house by this name on the Morden property and when Page purchased the estate it was pulled down 7 only to be rebuilt just outside the boundary of Wricklemarsh. But this is conjecture, for the important fact arising from Page’s purchase was the demolition of the old Morden mansion and the erection of Page’s splendid classical mansion Wricklemarsh House, designed by John James and sited roughly on the crossroads of what became Pond Road, Blackheath Park, and Foxes Dale.

Few details of Page‘s intentions of Wricklemarsh have come down to us but it can be deduced from the fragmentary records available that he was a very different landlord from the Mordens. Whilst they were happy to lease off sections of Wricklemarsh to farmers and let houses on the estate from time to time, it seems that Page decided that most of Wricklemarsh should be imparked. At the centre of the park, there was to be a mansion house and most of the small cottages nearby were demolished.

Additionally, James had acted as a master carpenter to St Paul‘s Cathedral: in 1715 took over as Assistant Surveyor under Christopher Wren and Succeeded the master as Surveyor to the Fabric of Saint Pauls in 1723 the year he designed Page's house. He failed to secure a post as one of the official surveyors to the Commissioners for Building Fifty New Churches in 1711 but had his designs for St George Hanover Square accepted. By the time he was appointed to the Commission in 1715 most of the church designs had been settled and John James' only real work was to complete the tower of St Alphege Church in his hometown of Greenwich and possibly. one or two minor church details in addition.

His known works solely his design and erected under his supervision are few in number. only two or three houses — including his own on Crooms Hill — and much of James~ architectural skill went into finishing Other designers’ schemes or making alterations to existing properties.

The mansion was “begun and covered ” within eleven months and Sir Gregory filled it with splendid furniture and over one hundred old master paintings. The Wricklemarsh estate, extending from Morden College to Blackheath Village and Lee Road (as they are now) had cost Sir John Morden £4,200 in 1669, and Page, who bought the main part excluding the College and its grounds for £9,000, is said to have spent £90,000 on the new house and grounds.

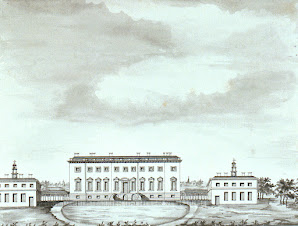

Why Page lighted on John James we will never know. but the decision must have pleased the architect. enjoying a Small reputation and into middle age with no distinguished monuments on his record at that time. Further. the architect must have been pleased that he had landed a client with no financial problems and prepared to spend Whatever the building cost. The end result was extraordinary and almost every factor in the Page mansion and its subsequent fate were faintly ridiculous. Unfortunately. We know little of the building of Wricklemarsh and not much more of Page's life there. A few fragments can be gleaned from official records the occasional reference in other men's memories and a handful of old newspaper cuttings. Also. no major Page archive has been discovered and few of the legal papers there are no documents relating to the erection of Wricklemarsh House. nor the plans and notes which must have passed between architect and client. The house. which was all demolished long before photography, is known to us through a handful of engravings. a few works of fine art and, mostly. amateur sketches. The contemporary written opinions were enthusiastic usually describing the house as one of the finest in England.

Newspaper reports claimed that the house was built within 11 months. that it cost anything between £90.000 and £120.000 and was. largely. erected in stone. In fact. Wricklemarsh was not of an unusual design. although the colonnades which led from the main block to the wings lifted the design scheme out of the ordinary classical style then fashionable for country houses. Horace Walpole, 4th Earl of Oxford (1717-1797) claimed in his “Anecdotes of Painting” (Vol. 4) published in the 1760s. that it had been inspired by Houghton Hall. This building had been designed in 1721 by Colin Campbell for Sir Robert Walpole (1678—1745). father of Horace. Even if this were so there is no reference to this in the later volumes of Vitruvius Britannicus a magnificent collection of engravings of Country houses and grand buildings. two additional volumes of which were published in 1767 and 1771‘ And it is from Vitruvius Britannicus that we get one of the most reliable descriptions of the house and the only surviving plans and elevations.

The accompanying description of the plates reads as follows: “The Situation is very pleasant. being in the center of the park on a rising ground. and commanding several extensive views. particularly from the north from ever the county of Kent. and from the south and east over Shooter’s Hill and Eltham. There is a basin of water on the north front, and another on the south front The first plate, which is a double one, contains the general Plan; the next is the plan of the principal and Attic floors to the north; the fourth is south front to the park, which consists of a tetrastyle Ionic portico, covered with a straight entablature, and finished With a balustrade; the fifth and sixth plates contain the flanks; and the seventh, the longitudinal section.".

Fisher’s Kentish Travelers Companion (the edition published in 1776) contains a curious story, worth repeating for it may have had some Elements of truth: “The seat of the late Sir Gregory Page is at the southeast extremity. of Blackheath, and in eleven months was this stately and elegant mansion raised from the foundation and covered in. Two causes are assigned to the amazing expedition with which so large a fabric was erected; one is that the baronet is reported to have been allowed the liberty of using a sufficient quantity of the materials prepared at Greenwich for the buildings intended to be added to that hospital (Now the Royal Naval College) ; and the other, that Sir Gregory Could purchase stones out of the same quarry from which the governors of that charitable institution expected to be supplied, when they, for a very obvious reason, could not procure them. And the fact is certain, that the works at the hospital were suspended during the whole year that the mansion upon Blackheath was building. The park, and kitchen garden without, and the masterly paintings, rich hangings, marbles, and alto-relievos within this house, command the attention of every person of genius and taste.”

workmen engaged in taking it apart — the then owner exploiting its structural content was reported as saying that the house was so well built “that it would have stood for several hundred years.”

What of Page's time in his new house. It was fitted out and furnished with great luxury: descriptions of fine marble floors, much god leaf superb mantlepieces, and fireplaces, not counting the large number of capital paintings, including works by Titian, Van Dyck Caravaggio, and other fashionable "old masters” of the early 18th century appear in many books but of the general day-to-day arrangements and what Page did with his

time we know little. He attempted to divert a watercourse in the middle of what was to become Blackheath Village in 1741 but was fined by the local court and instructed to replace the stream on its proper course. Page closed up an old public right of way called Mount Echo Walk 7 but was required to provide some other footpath. This act came about when Sir Gregory came to an arrangement with the Lewisham Parish officers to enclose part of the waste of Blackheath into his formal parkland. The present boundary of the old Page estate runs up Montpelier Vale and along Montpelier Row to the Princess of Wales public house and along in front of The Paragon. But in Morden's time, the boundary was not so neat. Most of the Paragon ground was part of the Parish of Lewisham waste and the triangle of Wemyss Road, Paragon Place, and Montpelier Row was variously claimed by the Royal Manor of East Greenwich and the Lewisham Parish.

Horace Walpole’s Letters Vol IX 1775 Sir Gregory Page left Lord Howe £8000 and £12,000 after his aunt Mrs Page’s death. In 1779 he writes “I was at Blackheath t’other morning , where I was grieved. There are eleven Vander Werffs that cost an immense sum: half of them are spoiled since Sir Gregory Page's death by servants neglecting to shut out the sun. There is another room hung with the history of Cupid and Psycho, in twelve small pictures by Luca Giordano, that are sweet. There is, too, a glorious Claude, some fine Teniers, a noble Rubens and Snyder‘s, two beautiful Philippe Lauras, and a few more,—and several Very bad. The house is magnificent, but wounded me; it was built on the model of Houghton, except that three rooms are thrown into a gallery. Now I have tapped the chapter of pictures, you must go and see Zoffani’s ‘Tribune at Florence,’ which is an astonishing piece of work, with a vast deal of merit. There too you will see a delightful piece of Wilkes looking—no, squinting tenderly at his daughter. It is a caricature of the devil acknowledging Miss Sin in Milton. I do not know why, but they are under a palm-tree, which has not grown in a free country for some centuries.”

By 1727 Lewisham’s claim seems to have succeeded for, in April of that year, the Parish officers granted Page the right to enclose the land but solely for herbage and grazing purposes 7 in other words, not for building thereon They charged him £410 a year and the term of the lease was to run for 1000 years; to confirm the agreement the Earl of Dartmouth (Lord of the Manor) agreed to the lease but charged Page only a peppercorn in rent. The area involved was just over 8; acres, although in February 1756 a little piece of tidying up to the north-east of the grant added another quarter of an acre.So far as we can tell, Page respected the terms of fire lease but, in 1784, when Cator purchased the estate from Sir Gregory’s heirs, the covenants not to build were either broken or bought off.

Gregory Page was to live half a century in his palace. He purchased the estate when he was only 34 years old and was to pass his prime years there and the inevitable decline into old age under its roof. He sired no children to our knowledge, so, except when there were visitors or cousins to stay, the house must have been an extraordinary home for just two people ~ Gregory and his wife, Lady Martha, attended by the handful of servants needed for their wants. It is claimed that Page entertained lavishly and that Wricklemarsh was often the venue for parties, balls and grand dinners, if that were so, then little description has survived in print. George II dined with Page a number of times, especially after a military review or pageant on the Heath — for example, after the Royal review of Kirk’s & Harrison ‘s Regiments in 1728. And there is a report of a grand wedding feast for Sir John Shaw, of Eltham in 1752, when he married a relative of Martha Page.

A letter published in Country Life (July 4, 1947) quotes a manuscript letter of Sir Henry Dryden, Bart, although without a date: “. . 'Page betook himself to commerce and lived with great splendor and hospitality at his noble mansion at Blackheath; indeed the princely magnificence of his residence, his Park, and his domestics surpassed everything in point of grandeur that had been exhibited by a citizen of London Since the days of the munificent Sir Thomas Gresham and almost equally the Italian merchants of the ducal house of Medicis,"

The end of the Page dynasty coincided With radical social and economic alterations: the death of Sir Gregory brought the era of the landed gentry to a close in the Blackheath area and prepared the way for a new style of proprietor: the speculative developer.

Sir Gregory Page, 2nd Baronet, died in August 1775; his remains were buried in

St Alfege Parish Church, Greenwich. alongside those of his wife, Martha. who

had died in October 1767. Page's will was complicated, made especially so

because he had produced no heirs and only his sister Mary (1702—1724) of the

five children of Gregory Page II, had borne any offspring. Gregory Page III died

immensely rich helped by the huge investments in land despite the cost of

building and furnishing Wricklemarsh as well as the landscaping of its parkland.

His will itemized many small bequests to relatives and a number to charity:

including £400 to the poor of East Greenwich, and £300 to Morden College Of

Wricklemarsh, the title passed along with all the other Page estates, to Gregory

Turner, his great-nephew, although the benefit of Wricklemarsh was to be enjoyed

by Page‘s sister-in-law Juliana until her death. Juliana (b 1701) had married

Page’s brother, Thomas who died in 1763. Juliana was the daughter of the Ist

Viscount Howe (1648—1712) and aunt to Richard, Admiral of the Fleet, 4th Earl

Howe (1726-1799) 7 who was appointed by Page as one of his executors. If

Juliana had been blessed with children, the descent of Wricklemarsh might have

been very different but. as it was, when she died in 1780, the entire property passed freehold

to Sir Gregory Turner (174771805), 3rd

Baronet of Ambrosden, Oxford, and grandson of Mary Page (1702—1724) and Sir

Edward Turner (1691-1735)

Part of the settlement of the Page estate on to Gregory Turner was a condition that

he take the name Page in order to

qualify for the inheritance. This modest requirement was met through Royal License and Gregory became Sir Gregory Page-Turner 3rd Baronet in 1775.

Meanwhile, the family was faced with the problem of maintaining the empty, It

was an enormous structure and must have

been hugely expensive to heat and clean, even for a rich man living in the

later quarter of the 18th century The

family most probably Mrs. Juliana Howe made several attempts to let

the property and a list of distinguished

names of tenants of Wricklemarsh survives today in the pages of Hasted / Drake they include George 4th Viscount Townshend

(1724—1807), whose extraordinary career

succeeding; James Wolfe-as Commander-in-chief at Quebec on the latter’s death

on the Heights of Abraham in 1759;- and he was to become Lord Lieutenant of Ireland in 1767. His tenancy of

Wricklemarsh coincided with his return to Royal and public favour after a

period of what has been described as “a great dissipation and corruption."

He was to occupy the Page mansion until 1778 when it passed to Henry 12th Earl

of Suffolk, (1739-1779) who probably died before establishing a local presence.

Lastly, the house was left to Edward Baron Thurlow (1731—1806) who was created Lord Chancellor in 1778. Thurlow was to remain at Wricklemarsh until

1783 although there is some small evidence that Admiral Sir George Young FRS, FSA

(1732—1810) an active supporter of colonies in Sierra Leone and New South

Wales, may have lived there in the last year of Thurlow’s tenancy.

Be that as it may: Juliana (Page) Howe had (died in 1780 and there was no longer

any necessity for Page-Turner to keep the estate. He was well endowed through

Turner and Page legacies and he lived in a perfectly adequate house on his own

estate at Ambrosden. The cost of looking after Wricklemarsh was unjustified for

the fashion for monster private palaces was over — revived only briefly in the

late 19th century by industrial and commercial barons.

Page-Turner had obtained the necessary Act of Parliament in 1781 to divest

himself of Wricklemarsh and, on 7 April 1783, the first of a series of auction

sales took place which stripped the house of its contents and sold the freehold

of the building and the attached estate with all its appurtenances, to the

highest bidder: John Cator Esq, of Stumps Hill Beckenham, for the seemingly

ridiculous sum of £22,550, and an additional £900 for the timber and £102 for unspecified fittings. The auction sales were

conducted by the well-known London house of Messrs Ansell & Christie, who

described the property as a: “noble and spacious freehold house and added the

rider that the pictures and furniture could be had by the purchaser on a

valuation. But, in fact, these were all sold at separate auctions.

The best description we have of Wricklemarsh in April of that year (1783) can be

found in the diary of Sylas Neville, edited and published in 1950 by Basil

Cozens-Hardy. Neville, a physician about whom little is known, kept a diary

for the years 1767 to 1788. Much of his doings were of no consequence but his

visits to Wricklemarsh are of interest here. On Tuesday, April 22, 1783, he

wrote: “In the summer of 1777 after seeing the Blues reviewed on Blackheath drove

to the late Sir Gregory Page’s magnificent seat in front of the Heath, which my

companion and myself wished to see, but could not get admittance. This day,

however, I saw it from top to bottom without asking the owner to leave. Sir

Gregory Page-Turner is quite broken down by his extravagance and the Trustees

have ordered everything to be sold — sic. transit gloria mundi. The house

stands high on the Heath. The South front is the best — has a portico with Ionic

columns. The offices are joined by a colonnade — every part of the building is

of stone.”

The interior was sumptuously fitted out and the house contained an art gallery comprising 118 paintings, among them works by Van Dyck, Rubens, Parmigiano, Veronese, Titian, Caravaggio, Poussin, Teniers, Brueghel, Wouvermans and Dou. No wonder that Sir Gregory was reputed to be the richest commoner in England.

Monday 28 and Tuesday 29 April 1783: “Two more visits to Wrinklemarsh (sic)

Park (Sir Gregory Page’s). Some things in the sale that I wished to pick up

and I have in fact succeeded. Walked all over the park a fine lawn and a piece of

water on the south and another with a basin on the north part but little timber

– did not see a single oak. Morden College looks into the park on the northeast. Two uncommon hot days Neville did not look very hard. A tree survey of

Wriklemarsh made by Page died shows 1466 trees (mostly elm and oak) with a total

length of 22,668 ft. and valued at £1086. John Rocque's plan of 1745-1746 shows well-organized

avenues of trees 7 clearly only the beginning of a grand landscaping scheme,

but. mature by the early 1780s.

But where Neville‘s report, must be questioned is in his claim that Page-Turner

was “broken down by his extravagance”. There is no other proof for this and

there is no reason to believe that the sale of Wricklemarsh was for any purpose

other than to rid the family of a real estate problem ~ a huge house, costly to

keep in good order, unwanted by any of the Page-Turners. The sale of property

at Blackheath consisted solely of Wricklemarsh, and even part of that was not

sold: the house and garden belonging to Edward Sadler in Blackheath Village

stayed in the Page-Turner ownership and their descendants until well into the

late 1920s, and there was much land at Westcombe, Eltham, and Kidbrooke which

was not sold. If" Page-Turner had been reckless and extravagant he would,

surely, have sold all the Blackheath estates in one sale, But Westcombe and

Kidbrooke were, it is true, subject to leases which may have prohibited a

profitable sale, quality land and able to command good agricultural rents, Cash

was needed to pay out certain settlements on the Gregory Page will and

Wricklemarsh was a suitable parcel to sell for this purpose.

It is interesting to speculate on why this 283-acre estate, boasting a house that

cost at least £90,000 to build 60 years before, should have been sold for as

little as £22,550. Curiously, this was close to the final valuation put on the

property by agents acting for the trustees. Their initial figure was £38,571 for

the house and £22,275 for 300 acres of land. This was revised to £10,500 for

the house, £14,150 for the land, and £1,000 for the timber.

The market for land at the time may have been depressed. Acts of Parliament

were needed for virtually any development of parkland, except on sites

traditionally held to be building land, so that the purchaser of Wricklemarsh was not buying something that could be exploited instantly. And it

is clear, from the price paid ~ down to an exact £50 e that the auction was a tight

run exercise. The purchaser — John Cator must have been successful by a wafer-thin margin of only £50 and it would be interesting

to know against whom he had been bidding. Alas, the records do not survive.

Lastly, we must remember that Wricklemarsh House in 1783 was a “white

elephant" massive to maintain, probably in need of substantial repairs,

possibly vandalized, and fit only for institutional use if an institution could

be found to take it on. Between the death of Page in 1775 and the months before

the sale vandals had broken fences and made much damage, In January 1784 a

survey found that the post and rail fences around the farm yard area of 1810 ft

in all had sustained damage costing £410 to repair. Because of this Cator’s

purchase price was reduced by that sum.

John Cator was from the South East, he lived in Bromley and purchased Beckenham Place in 1773 from the 2nd Viscount Bolingbroke (1743-1787). The Cator monies were derived from the timber business and landholdings. He was a shrewd businessman, cultured and well-connected. He was a friend of Samuel Johnson (1709-1784). Cator was also a Parliamentarian but undistinguished. He had always applied his capital wisely, mainly by the acquisition of land. In addition to Beckenham, he purchased plots on the southeast side of London, in particular Sydenham and the land which became the site of Crystal Palace.

When Cator purchased the Wricklmarsh estate. which subsequently which subsequently came to bear his name, he may have cherished a grand plan for its use, but there is no evidence of what that plan may have been. lt has been argued that Cator knew he had purchased a bargain but he had only a vague idea of the best means of exploiting the Old Page estate. The purchase had cost him £22,550 (£4.1 million) and for this he bought not only Wricklemarsh House but two or three small properties and the freehold of a farmhouse besides, about 272 acres of park and farmland (almost entirely in agricultural use), over four acres of clean water in the form of two stream fed lakes, and substantial frontage onto highways of a reasonable standard by the conditions then prevailing.

It is most doubtful whether Cator intended, in 1783, to develop his new estate or building. He had not done this at Beckenham (the family seat) and was not to do so at Sydenham, and it was four years before any development leases were granted by Cator in Blackheath and then only for a single house {Park House) built by Capt Thomas Larkins, in what became Cresswell Park (see Volume 1: Chapter 6). Another reason to dismiss the hypothesis that Cator intended from the outset to develop Wricklemarsh can be found in his endeavors to find tenants for the big house. He had no need of it for himself, for he lived at Beckenham, and Wricklemarsh House would have been a hugely expensive property to maintain in addition to, or even as a substitute for, the Beckenham Place residence. Cater had no children and his household would have been, therefore, quite small.

In 1783, shortly after the auction, Cator engaged in negotiations with the War

Office which caused Parliament to be asked to consider leasing Wricklemarsh

House as accommodation for officer cadets training at the Royal Military Academy, at Woolwich. Nothing came of this inquiry with the

exception of an extremely accurate survey of the estate, undertaken by the

Ordnance Department in that year. This provides us with a more precise map than

any before and, because Cator had sanctioned no development by this time it is

safe to assume that the 1783 survey (Now PROMPHH 570) can be read as depicting

the state of Wricklemarsh once Sir Gregory Page had completed his house and

park — roughly by the early 1730’s.

In 1785, the old Page mansion was leased to trustees of William Frederick, 2nd

Duke of Gloucester (1776—1834), the son of George III. Because William was only

10 years old at the time, the house was taken probably as a future Royal residence and the Prince may never have lived there

at all. Certainly, there were no leases encumbering the property by 1787

because Cater, unable to sell or let the house, did the next best thing he

pulled it down. It was dismantled with great care and the materials sold off at

a succession of sales which started on May 28th, 1787, and continued for the

next eight days. The newspapers reported that Captain Larkins had purchased

some of the materials for his new house Park House.

|

| In this detail a Cart can be seen loaded with salvaged stone while visitors walk through the demolished ruins. |

The value of the materials of Wricklemarsh were assessed at £14,000 which means that Cator would have recouped nearly two-thirds of his initial investment in four years, not counting any monies received from farmland rents and leaseholds, although these would not have added up to much in that time. Whilst the initial dismantling of Wricklemarsh had started in May 1787, the structural walls, especially on the east and west elevations of the wings were to remain for many years after that, and sketches survive, some dated as late as 1809, showing some of the skeleton of the house. Some writers have claimed that the ruins stood until 1823, but there is no evidence for this and it is unlikely that leases for building would have been granted for plots close to the site of Wricklemarsh in 1806 and 1809 if much of the old mansion had remained.

Fisher‘s Travelling Companion, for 1790, notes: “The seat of Sir Gregory Page, now pulling down, is at the southeast extremity of Blackheath . . . the house has been stripped of its interior beauties; and, what was some years since a mansion fit for kings, now appears to the eye of the traveler a mass of ruins”. The edition of 1799 notes: “The seat of the late Sir Gregory Page, now entirely pulled down,".

It is possible that some of the original house survives today, in foundations underneath the crossroad of Blackheath Park and Pond Road A better claim can be found in the barrel-vaulted cellars of a house called The Nyth, on the east side of Pond Road and behind No 49 Blackheath Park. The Nyth (built-in 1843) is sited directly on the site of the projecting east wing of the old house and may have been erected here partly to make use of part of the old Wricklemarsh cellars for storage and foundation. It is likely that The Nyth was built by the then-tenant of No 49 for a schoolroom or outhouse.

The greater part of Wricklemarsh was to remain in agricultural use and the old house of Sir Gregory Page was dismantled stone by stone, either legitimately or through vandalism and the elements. By 1808 there was practically nothing left bar two massive archways and a pile or rubble and broken rustication.

|

| The Royal Highness the Princess of Wales at the West Front of the Ruins of the late Sir Gregory Page's seat Blackheath |

The Ruins of Wricklemarsh attracted a number of artists who made paintings and drawings of the House, during the course of its demolition between the late 1780s and 1803 . Artists such as Joseph Mallord Wiliam Turner and others were attracted to its ruinous state. Examples of these paintings can be seen in the collection of Tate Britain and the New Walk Museum and Art Gallery in Leicester. The ruinous state of Wricklemarsh also attracted tourists who wanted to experience a sense of classical aestheticism. In the contemporary print above this included the Princess of Wales. Picturesque is an aesthetic ideal introduced into English cultural debate in 1782 by William Gilpin in Observations on the River Wye, and Several Parts of South Wales, etc. Relative Chiefly to Picturesque Beauty; made in the Summer of the Year 1770, is a practical book that instructed England’s leisured travelers to examine “the face of a country by the rules of picturesque beauty”. Picturesque, along with the aesthetic and cultural strands of Gothic and Celticism, was a part of the emerging Romantic sensibility of the 18th century.

Beckenham Place enlarged with salvaged materials from Wricklemarsh

John Cator was born on 21 March 1728 in Ross on Wye, Herefordshire, the son of John Cator and Mary Brough who were Quakers. John was the eldest of four sons and two daughters. The Cators had established themselves in Beckenham and Bromley by the 1760s In about 1762 John Cator married Mary (1730-1804) daughter of the famous Quaker botanist Peter Collinson (1694-1768). Their only child, Maria died in 1766 at the age of three John and Mary Cator are known to have traveled to Venice in 1770 (Ingamells) Cator made his first fortune in the timber trade; the business had been established by his father at Bankside in about 1748 and used his wealth to purchase and develop land in South London and Kent, notably at Wricklemarsh, where he purchased the vast estate and house of the late Sir Gregory Page in 1783 and undertook the developments now known as Blackheath Park. Manning suggests that Cator’s fortune was enhanced by activities as a financier as well as a timber merchant. Cator also took up residence within the new Adelphi development of Robert and James Adam in 1776. He lived at 5 John Street until 1782 when he moved to 7 Adelphi Terrace, the grandest part of the development. Cator’s circle of friends and acquaintances included Samuel Johnson, Hester Thrale, Fanny Burney and James Boswell and his character is invariably described using the following extracts of their writings about him.

|

| Fireplace at Beckenham Place, formerly from Wricklemarsh |

Cator has a rough, manly independence and understanding and does not spoil it by complaisance. He never speaks merely to please and seldom is mistaken in things which he has any right to know. There is much good in his character and much usefulness in his knowledge. (Johnson) He (Cator) prated so much, yet said so little, and pronounced his words so vulgarly that I found it impossible to keep my countenance (Burney) A purseproud Tradesman coarse in his expressions and vulgar in Manners and Pronunciation; though very intelligent, and full of both money and good sense (Thrale)

Cator had political ambition and stood as a member of parliament for Wallingford, Ipswich, and was Sheriff of Kent in 1781. In April 1784 he was elected MP for Ipswich but after a petition was presented to the House of Commons the election was set aside.

|

| Beckenham Place Portico with Columns & other elements from Wricklemarsh |

|

| Beckenham Place Portico in red constructed with salvaged stone from Wricklemarsh |

The house at Wricklemarsh plays an important role in the changes at Beckenham. It was built by the wealthy Sir Gregory Page to the designs of John James (c1673-1746) in the early 1720s. James' career was overshadowed by his more famous contemporaries such as Gibbs, Vanbrugh, and Hawksmoor but he remains a significant figure now best remembered for his collaborations with Hawksmoor at St Luke Old Street and St John Horsleydown. John Brushe’s account of his career sets his work at Wricklemarsh within its wider context, particularly highlighting the house at Wricklemarsh as being one of the great lost Palladian houses in the 1720s. Page assembled a major collection of artworks and was the founder of the Free and Easy dining club (DNB) Sir Gregory died in 1775; his heirs had no need of such an extravagant house and the estate was auctioned in 1783, the successful bidder being John Cator, whose principal motive was probably to undertake development on the land. After unsuccessful attempts to leave the house, Cator decided to demolish it and sell the materials. The first sale of building materials was advertised in the Times of May 1787 but it does seem probable that much of the shell of the house was still standing in 1810.

Lambert, writing in 1806 records that

“A great part of it has not yet been removed, and now

stands in ruins, a

melancholy monument of its former grandeur.”

|

| The entrance (north) front is largely the work of c.1810, incorporating material from Wricklemarsh |

|

| The Portico, the four columns from Wricklemarsh support a new pediment adorned with the Cator's arms. |

It seems well established that the north wing at Beckenham Place was constructed using salvaged material from Wricklemarsh, The columns to the portico are rather too large for the building they guard, but at 25 feet in height are a perfect match for the columns at Wricklemarsh. Comparison of the exterior of the north wing with engravings of Wricklemarsh suggests that a substantial amount of material may have been re-used including many of the window surrounds, the rusticated lower story, the niches, and columns flanking the entrance door. The partial inscription above the entrance door of Beckenham Place, of which ‘SANS SOU..” can be deciphered, is probably the phrase “SANS SOUCI” which translates as ‘free and easy’ and must be another survival from Wricklemarsh.

|

| East Elevation of North wing showing features from Wricklemarsh |

|

| Niches flanking the doorway contained statues & are likely to incorporate material from the entrance hall of Wricklemarsh |

|

| The main doorway is likely to be of adapted material From Wricklemarsh. Traces of the words “Sans Souci” can be seen on the Entablature. |

The survival of the shell of Wricklemarsh into the nineteenth century and the internal character of the extension make it far more likely that the extension was the work of John Barwell Cator, undertaken in the whirlwind of expenditure following his inheritance, to impress his new wife and family. Major expenditure on country houses usually follows a change of ownership. The wing has, within this report, generally been referred to as work of c1810 although no secure dating has been established. The new wing required the main hall to be approached along a rather long central corridor, with long rooms flanking it on each side. The overall impression of the new wing is that it was conceived as a showcase for masonry salvaged from Wricklemarsh, compromised by the levels existing within the original house. The pediment supported by the columns is visually too light and the rooms on each side of the central corridor are ill-proportioned. The additional accommodation was, presumably, welcome. The ground levels to the north of the house appear to have been raised during this phase of work to allow more or less level access to the upper ground floor. The contours of the land before this alteration are not certain but it seems probable that the original north entrance incorporated a large flight of steps. This raising of the ground, supported in part on the vaults below, also created sloping banks to the east and west which were then concealed below blocks of planting.

An Inventory of the contents of Wricklemarsh was taken between the 15th-22nd August 1775 on behalf of the executors (Sir Gregory Turner Bt and teh Rt Hon Lord and Lady Howe of the Late Sir Gregory Page 2nd Bt. The 70-page inventory lists all the effects of value contained in Wricklemarsh at the time of the death of Sir Gregory Page 2nd Bt.

Link to the Inventory of contents of Wricklemarsh 1775

Comments

Post a Comment

Please leave any interesting factual comments relating to the post(s)